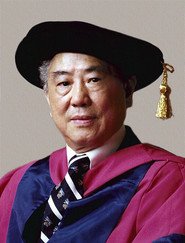

Mr Chancellor, I have pleasure in presenting Stephen Sze Fun Hui for your consideration in respect of the degree of Doctor of Laws honoris causa.

Stephen Hui was born sixty-eight years ago at Tsam Kong in Guangdong province. His early education was at Tsam Kong until he reached the age of fourteen when he arrived here in Hong Kong to further his secondary studies. He attended the Diocesan Boys School then at Ho Man Tin, and at that time a college of 600 pupils under the headship of the Rev CBR Sargent.

In 1926, Stephen Hui became a boarding student and as such was able to savour the flavour of close association with many people whose names are now extremely well known in Hong Kong's public life.

Leaving DBS, Stephen Hui decided to return to China and spent a very short period at Ling Nam University in 1933. He soon proceeded to Shanghai, however, for studies in civil engineering somewhat more to his taste. In those days the study of civil engineering was indeed somewhat different, not perhaps as specialised as today, and certainly quite innocent of computers.

In 1936, he took a fateful step: he set out for Colorado USA to one of the most fascinating areas of the world, geologically speaking. The Colorado School of Mines located appropriately at Golden, which he was to attend from 1936 to 1940, is truly a celebrated centre for mining studies.

In September 1940, at a singularly troubled time, Stephen Hui made his way back to Hong Kong. He had by this time become both an Engineer of Mines and a Geological Engineer. A double triumph indeed. He did not, however, immediately turn his attention to his first love, to geology, but rather to shipping. Initially, he became an assistant manager to the Shun Cheong Shipping and Navigation Company. Soon the Japanese invasion interrupted not only Stephen Hui's career but of course so many activities in Hong Kong.

Stephen Hui returned to China where he remained for the next eight years. These were years both of sadness and achievement. His own mine was destroyed by Japanese action in 1944 at a personal loss to him of a considerable sum and immeasurable anguish. Despite the trials, he might agree with Longfellow: "Let us then be up and doing, With a heart for any fate; Still achieving, still pursuing, Learn to labour and to wait".

Discounting the perils of the times, he became active in a number of fields related to geology and mining. Firstly, he became an exploration geologist and mining engineer on the noted Yan Liu Tung and Tai Hang Ling Coal fields, working for the Tin Pui Wing Coal Mining Company in Tai Po Liu Shing District. In the late forties he had become a Chief Mining Engineer in a mining district in Guangxi province.

Just twenty years ago, Stephen Hui returned to Hong Kong to develop an interest in non-metallic industrial metals and to take up a connection with the Yan King Mining Company with which he is still very much associated - as its Chairman and Managing Director.

Mr Chancellor, in commending Stephen Hui's cause to Your Excellency, I should mention his singular devotion to his chosen profession - that of engineering geology. It is, Sir, becoming daily more apparent that twentieth century man relies upon minerals in a way unimagined to earlier generations. Without the products of earth and to the deep-delved earth, our civilisation as presently constructed might well collapse. This is a situation which Stephen Hui has sought at draws to the attention of the Hong Kong public. From Mother Earth we derive a vast richness of fruits, vegetables and minerals which alas, we may at times be seen to be plundering.

Minerals have, to an unexpected extent, he will agree, inspired imaginative commentaries. Romantic poets naturally were romantic about the fruits of the soil. Keats informs us:

"The poetry of earth is never dead, The poetry of earth is ceasing never..." Again, a more utilitarian approach was Masefield's "dirty British coaster" which carried mineral products: "coal, road-rail, pig-lead, ironware and tin trays".

How then might we evaluate minerals? Kipling argued a sequence: a somewhat idiosyncratic set of priorities;

"Gold is for the mistress - silver for the maid - Copper for the craftsman, cunning at his trade, Good!' said the Baron sitting in his hall, But Iron, Cold Iron - is the master of them all."

Not everybody, Mr Chancellor, will agree. We can find other less glamorous but equally important candidates for the position of top mineral. Tungsten and Molybdenum are near the top of Stephen Hui's list.

Mr Chancellor, I leave the last poetic word on minerals with Shakespeare who makes the page in Richard III utter the following devastating comment adversely against Public Orators: "Gold is as good as twenty orators".

Non-geologists of course do not always understand the ways of the geologist. Sir Walter Scott, for example, mistook the geologist's enthusiasm with a hammer for some sort of frenzy. He said: "They knap the chunky stones to pieces like so many roadmenders gone mad". A modern geologist like Mr Hui has been authoritatively described as "a person who employs many of the tools of modern technology in order to understand the history and composition of the earth". The simple hammer has given way to what is called "demonic rock crushing", which has added a degree of precision unknown in Scott's day. The extra facility of modern laboratory techniques has immeasurably improved our understanding of the earth's structure and processes. Non-geologists too, do not always understand now critical is the struggle to avoid a mineral famine. Mr Hui's speeches are full of a keen concern for the rate of man's mineral consumption and the discovery or replenishment of the goods of the earth. We hear dramatic expressions, such as "rape of the earth", "plunder of the environment", and indeed, Sir, the politics of raw materials is the raw material of international politics. On a less elevated plane, I venture to suggest that many young people, geologists and otherwise, often appear to interpret rock as a rhythmic rather than as a geological phenomenon.

Mr Chancellor, it is the mission of Stephen Hui to advance our knowledge in his chosen field of study. He has given much of his time, energy and resources to the education of the Hong Kong public in matters mineral. On October 5, 1979 he donated to the Hong Kong Museum of History, a large set known as the World-Wide Mineral and Rock Collection as well as other sets of his mineralogical collection. In his speech on that occasion, he drew attention to the rapid exhaustion of molybdenum and tungsten. Both have high temperatures before reaching melting point, the latter of use in, for example, armour plates and gun-barrels. This is, perhaps, a sad bellicose commentary on man's use of metals. For his work, Stephen Hui has been given well-merited recognition both in Britain and in the USA. In the latter country he was awarded a medal of distinction by his old college, the Colorado School of Mines, and was the first person from East Asia so to be honoured. In 1979, he was made an Honorary Fellow of the Institution of Mining and Metallurgy in Britain, once again obtaining a rare, indeed virtually unique, distinction for Hong Kong geological engineers.

We saluted these achievements in 1977 in admitting Stephen Hui to our University Court. Today we go one step further - to award him our doctorate degree.

Mr Chancellor, for his continuing concern to educate us in the good husbanding of the resources of the earth, as well as for his science, industry, philanthrophy and generosity towards this University, I call upon you to award Stephen S F Hui, the degree of Doctor of Laws honoris causa.

Citation written and delivered by Professor Peter Bernard Harris, the Public Orator of the University.