Mr Pro-Chancellor, I begin with a story - not of one woman, but of two. In a school in Hong Kong, two teachers - one English, one Chinese - are quarrelling, with some bitterness. The English woman is attacking her colleague for using the Cantonese vernacular in school. The Chinese woman resents what she regards as a colonizer's attitude. The teachers take their quarrel to a third woman - to Joyce Bennett. What is the verdict: who is to be justified? Joyce Bennett's verdict is not to say that the English teacher is right, not to say that the Chinese teacher is right, but - simply - to weep. In the next day's sequel the English teacher apologised to her colleague. Did Joyce Bennett weep then because of the bitterness that can divide human beings? Did she weep because Hong Kong suffers from such bitterness? Did she weep because teachers could regard their quarrel as more important than their students? Did she weep because she felt in her own self the urge to quarrel? At all events, she was known as an open-minded and forgiving person, who encouraged her students to be the same. Joyce Mary Bennett was born in London in 1923. She studied at Burlington School, where she became head girl. She took a degree in History, followed by a Diploma in Education and a missionary training course. In 1949, she arrived in Hong Kong, and began her career in teaching here at St Stephen's Girls' College. Twenty years later, she would found St Catharine's School for Girls, Kwun Tong. And last year, after fifteen years devoted to that school, she retired from this work, and returned to England.

That, Mr Pro-Chancellor, is a simple account of her life. But it is, of course, too simple. For during the thirty-four years that she was in Hong Kong. Joyce Bennett did much. The public record is well known; Missionary, Principal of St Catharine's, priest in the Chinese branch of the Anglican Church; member of the Legislative Council, of the UMELCO police group, of the Advisory Committee on Corruption, of the Juvenile Courts Advisory Panel, of the Kwun Tong Area Committee, of the Public Accounts Committee, of the Widows and Pensions Scheme Committee, of the Court of this University, and of numerous other public and charitable bodies, appointed Justice of the Peace in 1976, and awarded the OBE, in 1978. She spoke and campaigned publicly on numerous issues: she was a leading advocate of the provision of nine years' free education for all, she spoke for the improvement of sub-vented hospitals, for the improvement of educational facilities for the disabled, on juvenile crime, on the conditions of teachers, on the school inspectorate, against the system of "bought places" in secondary education, on the importance of remedial teaching for slow learners.

And I believe, Mr Pro-Chancellor, that there was a source for all these actions, for this public record, and perhaps the same source for the tears she shed for the quarrelling teachers. Chateaubriand wrote: "Le christianisme, toujours d'accord avec les coeurs, ne cornmande point des vertus abstraites et solitaires, mais des vertus tirees de nos besoms et utiles a tous." (Christianity, always true to the heart, commands no abstract and solitary virtues, but virtues resulting from our needs, and useful to all) Useful to all, Mr Pro-Chancellor, but above all to the young. This is how Joyce Bennett seems to us. Here is a parable of that usefulness. It came to light that two girls of poor families were lost. This did not mean that they could not find their way to school - it meant, in all probability, that they had found their way to the bars of Tsim Sha Tsui. But Joyce Bennett did not - in "abstract virtue" - simply lament this fact. Rather, in person, she tried to track the girls down. In the event, both girls came back to the fifth form at St Catharine's. Embarrassed at first, giggling behind her school books, one girl was soon won back, and anxious about her chances of admission to the sixth form. It was Miss Bennett, again, who saw to it that the girl was admitted, and this same girl later went on successfully to a career.

I began, Mr Pro-Chancellor, with a story of two women. Turn your eyes from that scene of tears some years ago in Hong Kong, to another happier scene - this year - in London, and to another pair of women. A few weeks ago, Westminster Abbey saw a ceremony in honour of Florence Li Tim Oi, to commemorate her ordination forty years earlier by Bishop Hall, an ordination later called into question by the Church hierarchy. Joyce Bennett herself was, of course, ordained priest by Bishop Baker in Hong Kong in 1971, an event which marked an epoch in the history of the Anglican church. But she always insisted on the priority of Li Tim Oi. Turn your eyes, then, Mr Pro-Chancellor, to Westminster Abbey, to Joyce Bennett, priest, delivering the address of honour, and to the Reverend Florence Li, who reads the Gospel in Cantonese, and contrast that happy scene with the earlier quarrel between teachers. If I were allowed a word of that same vernacular, Mr Pro-Chancellor, I should perhaps say: very roughly - "Inthis world, we are all brothers": or, more fittingly, "In this world, we are all sisters and brothers".

Our ceremony today is not a religious one. It involves an ordinary human honour, and an honour to a human being, not a paragon. One of Joyce Bennett's lower sixth form pupils wrote of her as follows in the School Magazine: "Of course, she is not a person of all virtues, neither is anyone else. Sometimes, she is rather impetuous, and sometimes irrational."

But any absent virtue, surely, must be a lack of what Chateaubriand slightingly called "abstract virtue", any impetuousness surely a result of the desire to be useful, any irrationality surely the lineament of a heart in the right place.

I began, Mr Pro-Chancellor, with an allusion to Joyce Bennett's tears, but she is known as a person who is always smiling, always joyful. I venture that if you now turn your eyes towards her, you will observe that same smile on her face. At a speech day in 1982, she said: "Life is to be enjoyed, and school too must be enjoyed. I want the girls at St Catharine's to have happy school days. Nothing pleases me more than to be told by visitors who watch the girls studying, 'But the girls here are so happy! That is as it should be."

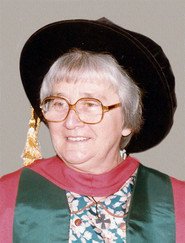

Mr Pro-Chancellor, for her contribution to education and social services in Hong Kong, I present to you the Reverend Joyce Mary Bennett, OBE, JP, always modest, always pioneering, always useful, always smiling, for the conferment of the degree of Doctor of Social Sciences honoris causa.

Citation written and delivered by Professor Francis Charles Timothy Moore, the Public Orator.