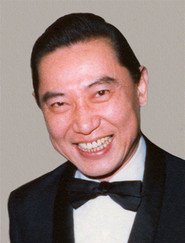

Mr Chancellor, I have the honour to present to you Fou Ts'ong for the award of the degree of Doctor of Letters honoris causa.

Mr Fou was born in Shanghai in March 1934 and into a distinguished home. His father, Fou Lei, was known as a celebrated scholar, and amongst many other things, a translator of European languages into Chinese. So celebrated was he that some Chinese scholars have suggested that Mr Fou Senior's translations actually bear comparison with the originals.

Mr Chancellor, I make this observation in order to show the context background of letters in which our proposed graduate was raised. This is the humanised and humanising home. Like many other young people in Shanghai, Fou Ts'ong studied the piano, firstly with a kindly lady teacher, as he remembers her, and, for a short period of about three years, with the somewhat more serious Mario Pad, until the latter's death in 1946.

At that time, Shanghai was a cosmopolitan city full of music. There were in Shanghai Italians like Paci as well as Russians and a number of Jewish refugees. What Fou Ts'ong felt however was the need to be receptive to these influences, but above all to be natural and indeed to discover his own individuality. He set off for university, to study foreign languages, but will freely confess that he was not at that time unduly diligent in all his studies.

Somewhat unexpectedly, Mr Fou found a way forward. He was asked to play piano in choral performances and his playing very obviously produced an astonished reaction. At this stage, Fou Ts'ong believes that he learned something about himself. His talents were, I stress, natural and he felt that if he would only permit his naturalness to develop then he could realise himself. He began to give concerts in Shanghai, and was eventually nominated to enter the 1953 Bucharest Piano Competition. He won Third Prize in Rumania and subsequently toured and performed in Germany and Poland.

Fou Ts'ong was now drawing the attention of a large and appreciative audience, in particular because of his interpretations of Chopin. In the very heart of the land of Chopin - in Poland itself, Fou was invited to take part in the Fifth International Chopin Competition. The result was that in 1955, Fou Ts'ong took Third Prize and distinguished himself particularly for his playing of the mazurka - that tone poem of the Polish dance - for which he won the coveted First Prize. The mazurka proved to be the perfect vehicle for his essential naturalness. However, Chopinist supreme that he intrinsically is, he had yet to complete his musical education. As a result of his proved mastery, Fou Ts'ong was awarded a scholarship to the Warsaw Conservatory. With growing confidence, he spent four years in Poland studying under Professor Drzewiecki ultimately being the recipient of the Conservatory's top award. These years in the fifties were the years when Fou Ts'ong's promise began to emerge. He gave five hundred or so concerts in Eastern European countries.

Fou Ts'ong now decided to live in the West and he left Warsaw in 1958 to settle in London. London now offers him a base from which he makes frequent forays on tour. Indeed he is engaged in travelling for several months each year visiting, for example, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and the Americas, North and South - and I am pleased to say finding Hong Kong a congenial place for a number of visits.

In recent years and particularly since the late 1970s, he has re-established many musical links with his homeland, China. He serves as a Consultant to the Shanghai Music Conservatory and to other institutions in Beijing.

Mr Chancellor, Fou Ts'ong has been at pains to find his intellectual roots - not merely as a musician, as a musician of genius - but also in a broader sense. Some time ago he gave an interview to a journalist, and this provided a fascinating glimpse of our graduand as he played in Beijing on his original grand piano, after an interval of some twenty years. The report subsequently described him as being dressed "in a turtle-neck sweater": "Chopin scores", we read, "were stacked on the piano along with a bowl of tangerines (which) some Chinese admirers had sent as a present".

The Chinese heritage is naturally strong. Fou is quoted as saying: "Chinese people are very kind, they have a Mozartian quality, a natural charm". What came through was the conviction of Fou's inescapable pride at being a member of the world's "oldest and possibly greatest civilisation".

Fou's own sense of Chinese culture - including plays as well as music - is that these things could be said to reflect a mediaeval outlook. Chinese culture, he thinks, has the best qualities of mediaeval art. It may not offer the individual assertion say of Beethoven, but it has age, depth and relevance to natural things. In ancient China there are six arts, let us remember, with propriety and music at the head.

Fou's own musical affiliations can be understood through a triad of great composers, Mozart, Chopin and Debussy. Mozart, the first, he believes clarifies issues, directly and simply, without frills. Indeed, Mr Chancellor, Mozart's life was short (thirty-five years) and often quite unspeakably miserable, and yet, the artistic genius of Mozart was of a sublime nature, transcending the dross world. Chopin, the second, was the self, the suffering, pain, anxiety, the trauma of everything that Chopin characteristically felt. Once again this is experienced by Fou with an expression which is exquisite, relevant and, essentially, natural. Thirdly, in the music of Debussy, Fou has found a cultural liberation. This is most clearly evidenced in the piano works of the great French master. We progress with Debussy from the French to the Universal, via the Etampes to the Etudes. We may go beyond a culture to appreciate a world culture. Once you have made all these progressions via order and technique, there is a chance to allow the natural to appear. Fou Ts'ong believes that Handel shows it, Mahler shows it and Debussy shows it. To very few musicians is it given to make such an intellectual odyssey. To Fou Ts'ong it is so given. Like Claudio Arrau he understands the truth beyond technique. Sir, technique is necessary and he has it in full measure. But he is also a natural pianist, born with tone and technique whose fingers naturally and automatically resolve any patterns no matter how difficult. Pianists of first quality produce a sound which makes one forget the piano is a percussive instrument. It is, it has been said, the product of a number of attributes, part muscular, part a projection of personality and part an ability to hear oneself. Writing in 1960, Herman Hesse said of Fou's playing of Chopin that he surpassed the previous masters, Padereweski, Fischer, Lipatti, Cortot. Indeed hearing Fou, he said, was to hear the "pure gold" of Chopin himself playing. Speaking of his playing, Hesse said: "It breathed the fragrance of violets, of rain in Majorca and also of exclusive salons, it rang of melancholy and rang of modishness, the rhythmic definition was as sensitive as the dynamics. It was a wonder."

Mr Chancellor, our graduand today would no doubt subscribe to Nietzche's dictum that "Life without music would be an error". We salute Fou Ts'ong as a master, able to make the piano sing, but also making its message one of clarity and steadiness with a sure feel for rhythm and line. Truly, we must think of Fou Ts'ong when we remember the dictum that there is on earth but one unpunished rapture, and that is music. The pianoforte has intrinsic powers to reach the depths and project the passion in human nature. Pianists impress the non-pianists (and even occasionally their brother pianists) with their pianistic skill. Through the technique the art emerges as an electrically charged running voltage of sound; a splendour of rapidity across the octaves. The virtuoso reveals the strength of wrist and finger as well as dexterity and suppleness. For his music the pianist requires, to recall the words of Wagner, a heart of fire and a head of ice.

The Chinese pianist has, of course, an added dimension. His piano can be the medium through which he communicates across the cultures. The pianist has, unlike performers on other instruments, a sort of autonomy. Fou must be capable of taking on the whole symphony orchestra, leading it on, cajoling it, taming it. And yet at the same time the piano is a solo instrument par excellence. The piano is the prince of instruments: A master of that instrument is the conductor of his hearers to heaven, for hell, as Bernard Shaw said in Man and Superman, is full of musical amateurs. Mr Chancellor, Mr Fou sees himself at least in the process of restoring himself to the vastness of Chinese culture. In this sense, he is truly a man of the arts, of letters. A pianist is, of course, a musician but not all become artists. Fou Ts'ong is very much a man of letters broad and catholic. For he will listen to English Tudor Renaissance music by way of contrast to more immediate musical concerns.

He must, however, be heard in person - as we will be privileged so to do within the next few days. Let us recall Celibidache's dictum that you may can peas but not music.

Mr Chancellor, in witness of the recognition of a great Chinese poet of the piano, and as a measure of our admiration for his sublime musical accomplishments in the past, now and to come, I call upon you to confer upon Fou Ts'ong the degree of Doctor of Letters honoris causa.

Citation written and delivered by Professor Peter Bernard Harris, the Public Orator of the University.