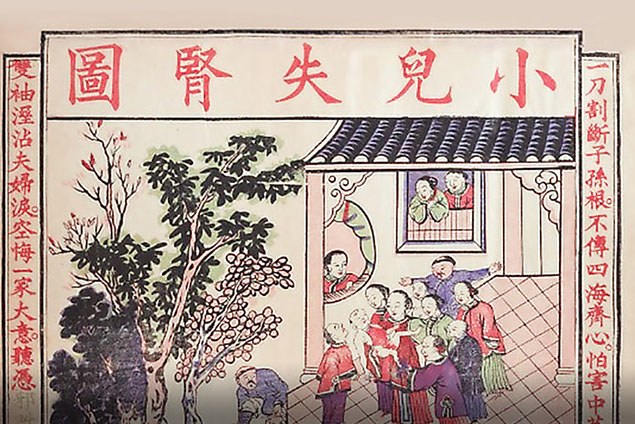

Extraction from pamphlets in 19th-century China illustrating children’s kidney being removed.

(Photo courtesy of Princeton Library)

Extraction from pamphlets in 19th-century China illustrating a child’s kidney being removed.

(Courtesy of Princeton University Digital Library)

Grisly Rumours And

Secret Spaces

Tales of Western medical missionaries gouging out the eyes, kidneys and other organs of Chinese were rife in 19th-century China. These rumours were fuelled not only by politics, but also cultural differences about medical practices, privacy and space, says Dr Tian Xiaoli.

Western missionaries who came to China in the 19th century to spread the Gospel and medical know-how may have raised the hackles of Chinese officials over their political intent, but local Chinese villagers were disturbed by something altogether more relevant to their daily lives.

As Dr Tian Xiaoli of the Department of Sociology has shown in her research on rumours, these foreigners brought strange medical practices and occupied space in ways that looked secretive and threatening to local populations. The resulting tensions triggered ugly rumours and exploded into violence, leading to more than 800 attacks against missionaries.

“Previous scholars have tended to explain Chinese hostility towards foreigners as anti-imperialism or nationalism against the invaders. I’m saying that while that might be true, how does this anti-imperialist sentiment work at the local community level?

“The most obvious way the missionaries showed themselves to the local people was in the space they occupied, which was different from the Chinese way of understanding space,” said Dr Tian.

![]() The missionaries did not think they were doing anything wrong, but the Chinese had their own understanding of what a medical procedure looked like and what practices might be considered secretive, which to them implied evil..

The missionaries did not think they were doing anything wrong, but the Chinese had their own understanding of what a medical procedure looked like and what practices might be considered secretive, which to them implied evil..![]()

Dr Tian Xiaoli

Miracles and closed doors

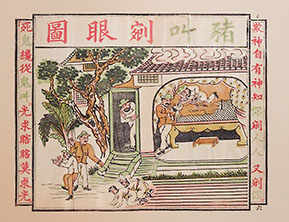

The missionaries introduced new and seemingly miraculous medical procedures, in particular eye surgery to remove cataracts and restore sight. But they took patients into separate rooms for treatment, away from their families, which violated Chinese norms about the visibility of medical practices.

The use of church space was also problematic. Church doors were always closed, contributing to the impression that the missionaries’ practices were not accessible to Chinese. This contrasted with the Buddhist and Daoist temples in the community which were always open. Moreover, women and men worshipped in the same room, which was unheard of in Chinese society.

“The missionaries did not think they were doing anything wrong, but the Chinese had their own understanding of what a medical procedure looked like and what practices might be considered secretive, which to them implied evil,” she said.

While the missionaries were not deliberately being secretive, the collision of different spatial concepts led to ambiguous information, which in turn led to dark speculation. Eye-gouging rumours may have been inspired by the eye surgeries, but other rumours were also common at the time, such as stealing kidneys (which are linked to reproduction in traditional Chinese medicine) and raping women.

Extraction from pamphlets in 19th-century China illustrating the practitioners of Christianity gouging out the eyes.

(Courtesy of Princeton University Digital Library)

Tianjin massacre

Dr Tian found evidence of these concerns in an analysis of 207 anti-missionary pamphlets from the 19th century, in which the overwhelming majority mentioned the missionaries’ medical practices and use of space.

Most remarkably, she found that even when the rumours were officially refuted, they did not die down. This happened in the famous Tianjin massacre of 1870, which marked an end to the cooperation between China and the Western treaty powers.

Rumours began circulating that missionaries in Tianjin were buying children and gouging out their eyes to make medicine, after nuns at a Catholic church offered a small reward for bringing homeless or abandoned children to their orphanage. An outbreak of disease then led to the deaths of many children and the nuns were seen hastily burying the bodies. It was assumed that happenings in the church killed the children, so mobs attacked. They slaughtered more than 50 foreigners and Chinese converts and burned foreign buildings, including churches, to the ground.

The sensitivity of the case led the Chinese Government to send a leading official, Zeng Guofan, to investigate. He reported that the rumours were false and persuaded the throne to issue an edict declaring this. However, few people accepted the ruling, which led to Zeng’s downfall. Rumours of organ-snatching by missionaries continued to circulate in China up to the 1930s.

“What I’m trying to say about these rumours is that everybody is innocent. The Chinese had reason to believe the missionaries were up to something, but the missionaries were in fact not trying to hide anything,” she said.

Nonetheless, the persistence and nature of the rumours were evidence that the missionaries’ practices offended deep cultural norms about spatial and medical concepts. Dr Tian said: “If people coined rumours just because they hated foreigners, presumably the rumours would take many different forms; you would expect diverse content. But when you look at the pamphlets, the content is very similar: they all relate to medical practice and space, and how people understood foreigners’ activities.”

Apart from shedding light on anti-missionary sentiments in 19th-century China, Dr Tian’s focus of space also offers a new way of looking at how people respond when two cultures come into contact, and how cultural norms influence their encounters.