In Hong Kong there has been a lot of soul searching about the role of local art producers. Is our success mainly in terms of an elite global audience or is something being given back to locals?

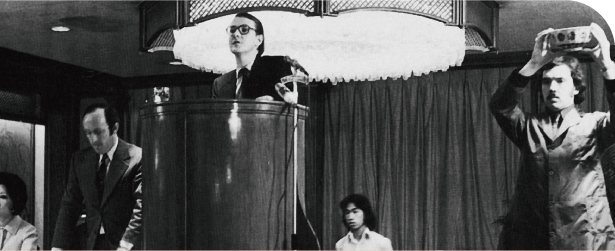

Dr Tang Ling-yun

Art Basel, the international art fair, staged its first show in Hong Kong in May this year, attracting tens of thousands of visitors and giving official recognition to Hong Kong as the world’s third largest art market, behind only New York and London. That status was achieved only in the past few years and people are still trying to digest what it means.

Dr Tang Ling-yun, Assistant Professor of Sociology, has been studying the Hong Kong art scene, focussing on networks and interactions between individuals and institutions and the effects of globalisation on art.

“In Hong Kong there has been a lot of soul searching about the role of local art producers. Is our success mainly in terms of an elite global audience or is something being given back to locals?” she said.

At first glance, the global audience, and those who serve it, are easily winners. Top galleries from around the world are trying to find commercial space here and although the high costs have deterred some, “everything has become more exclusive, more elite, more commercial,” she said.

Tough times for local artists

Local artists have paid a price, though. First, they struggle to find affordable space for studios – a problem faced by artists in many cities, but made that much worse by Hong Kong’s high cost of living.

“When I talk to artists, they keep coming back to space and real estate. It impacts their decision on whether to become an artist or not and it affects the kind of work they do. They say they focus on smaller-scale paintings because they don’t have floor-to-ceiling space for larger paintings,” she said.

Moreover, global preferences for contemporary art from Mainland China mean local artists are under-represented in local galleries, restricting their exposure.

“One comment I have heard from a lot of people is that Hong Kong galleries have a lot of ‘red smiling faces’ and political art from the Mainland. Young Hong Kong artists are not as interested in doing something so overtly political. They do more personal work and they don’t care about these trends.”

Local artists have difficulty in finding affordable space for studios and industrial buildings have become an alternative. Art studios in Fo Tan have thereby formed a unique art community.

Local artists have difficulty in finding affordable space for studios and industrial buildings have become an alternative. Art studios in Fo Tan have thereby formed a unique art community.

Formerly a slaughterhouse, the Cattle Depot Artist Village was renovated and developed into a village for artists in 2001.

Formerly a slaughterhouse, the Cattle Depot Artist Village was renovated and developed into a village for artists in 2001.

But more choice

Nevertheless, the international nature of Hong Kong’s art scene is not so bad for one local group – the audiences.

There is more choice than ever, driven by Hong Kong’s attractions as a free port with the rule of law and low taxes. Both contemporary works and antique pieces are often displayed in galleries and exhibitions for anyone to view, so the recent boom in the art market has brought wider benefits to the public.

“What we can say is that in having all of these different artworks for sale or enjoyment, for people to see and feel and experience, the scene has become much more pluralised. Art is now part of the bigger boom in the luxury market where people have all these options that they didn’t have before,” she said.■

(Courtesy of Sotheby’s)

Antiques had a head start

Chinese antiques are proving as popular as contemporary Chinese art in the global marketplace, and Hong Kong has had a central role in that development, too.

Dr Tang has also been researching this aspect of Hong Kong’s art market, which has roots stretching back to the 1940s, especially from 1949 when many collectors fled turmoil in China and came to Hong Kong. They brought their antiques and antique appreciation practices with them, and provided fertile ground for the development of a global centre for Chinese antiques.

“The auction houses started coming here from 1973 because Hong Kong had a group of people who were already interested in collecting and it was seen as a good place to do business, although there was some trial and error involved. The auction houses themselves made the buying and selling process much more transparent because they were publishing prices,” she said.

The flood of antiques onto the market after the Cultural Revolution and open-door policy of 1978 were an enormous boost to the market, and Hong Kong was well placed to take advantage of that. The 1980s were a golden period that laid the foundation for Hong Kong’s current success at the heart of the Chinese antique market.

“Hong Kong has played a very important role in globalising the collecting of Chinese antiques,” Dr Tang added.