When Dr Koon Yee-wan, Associate Professor of Fine Arts, first gazed at the paintings of Su Renshan, with their thick black angry calligraphy, her reaction was immediate.

“I thought they were the ugliest paintings I’d ever seen. He knew how to paint and I didn’t understand why he would make his paintings this way,” she said.

The jolt of that reaction, though, led her down a path of discovery. She came to see that Su had a wider significance than her initial response gave him credit for. “I realised he was a very angry man. And the idea of anger in Chinese painting is something completely different from before.”

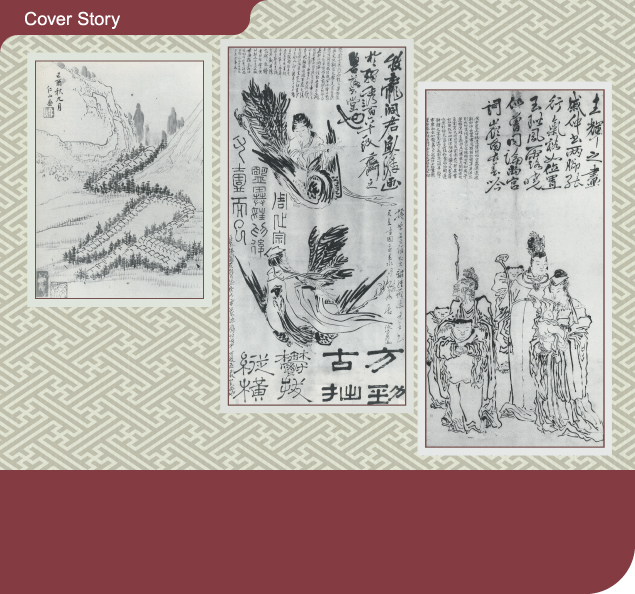

A portrait of Wang Anshi by Su Renshan

A portrait of Wang Anshi by Su Renshan

Su was of the scholarly class, but he had a contrary temperament. He failed his exams and refused to take them again, and some years later his father had him imprisoned for filial impiety for reasons that remain unclear.

More importantly, he was working in a time of turmoil. China had suffered humiliating defeat after the First Opium War in the 1840s and southern China, where Su lived, bore the brunt of the effects. The area was also plagued by pirates. With all this going on, Su had little regard for the Confucian values expected of an educated man of his times.

“He was a self-imposed outsider. He questioned the whole system of education and he made lots of angry paintings with calligraphy saying Confucius was a robber, a thief, a bandit who opened the doors to hell.

“He’s generally known as a madman or genius who was responding to the times and who saw the need for change,” Dr Koon said.

New twists on an old art form

Su’s response included bringing new ideas and forms into his paintings that challenged the value of traditional ink painting at the time. Apart from writing long, irate commentaries about Confucius, he adopted strong graphic images such as zigzags and circles for things like waterfalls, and played with conventional images. Women had a special place in his paintings because he thought they should have a more important role in society. In one painting, he depicted the traditional Chinese New Year gods as women.

“I wouldn’t call him a feminist because that idea didn’t exist then, but he was challenging the status quo of accepted beliefs and long-held values that had been going on since the 12ᵗʰ century,” Dr Koon said.

She believes his daring work could be a missing link in Chinese art history between the traditional style that prevailed during the late 18ᵗʰ century and the modernist vibrant art that emerged in Shanghai in the 1860s. Su’s unusual style and location made him an ideal candidate to bridge the two periods.

Political turmoil aside, Guangzhou in the 1800s was a hub of commerce and merchants were emerging as the main patrons of art, as opposed to the imperial court which continued to favour landscape painters. Merchants also had more money to spend and travelled to Shanghai and other ports.

“I think Guangzhou was very active in the transition away from the landscape literati tradition. Art that is less literati-based, more colourful and draws more on folk traditions and auspicious images has always been patronised by merchants,” she said.

He’s generally known as a madman or genius who was responding to the times and who saw the need for change.

Dr Koon Yee-wanA man of his times, and all times

A Defiant Brush – Su Renshan and the Politics of Painting in Early 19ᵗʰ Century Guangdong, written by Dr Koon Yee-wan, will be published by Hong Kong University Press.

A Defiant Brush – Su Renshan and the Politics of Painting in Early 19ᵗʰ Century Guangdong, written by Dr Koon Yee-wan, will be published by Hong Kong University Press.

This art has generally been ignored by art historians, who typically regard 19ᵗʰ century Guangzhou as a centre of ‘export art’ – of oil paintings depicting life in China aimed at Westerners interested in knowing more about the country or collecting souvenirs – rather than a place of serious art.

But Su was a serious artist and Dr Koon said his blending of classical and modernist styles made him a pivotal figure in the transition to the Shanghai art scene.

Interestingly, his work re-emerged in Hong Kong in the second half of the last century, when exhibitions of Su’s paintings were held in the wake of the 1967 riots and again in the approach to the handover. Tellingly, these were times when people were contemplating their Cantonese identity.

“He becomes a nice mouthpiece for a claim of individuality because that was what he was doing in his own time and it resonates with people,” Dr Koon said.■