Teapots celebrating the repeal of the Stamp Act, produced in England for sale to the American colonies in 1766 or after, suggesting the importance of the American export market for British manufacturers. Tea was a popular drink, not yet politicised at the time.

John Adams, signatory to the Declaration of Independence and future American President, forgot one thing before heading to the Continental Congress in 1774. He forgot about tea. At the Congress, Adams would support resolutions by the 13 colonies to boycott British goods (including tea) and implement other resistance efforts. But just before launching his journey there, he decided to stop at an inn for refreshments where he ordered his usual cup of tea.

Such mixed signals about tea are the subject of research by Dr James Fichter of the European Studies programme, who is putting finishing touches to the book Tea´s Party: The Politics of Tea in the American Revolution, 1773–1776.

THE POLITICS OF TEA

The Boston Tea Party is an enduring symbol of American independence, as the founders of the modern-day Tea Party showed when they named their political movement. The thing is, it was a far more self-serving and ramshackle affair than most care to acknowledge.

The famous Boston Tea Party occurred when patriots dumped the tea of the East India Company in the harbour in late 1773 to protest against the lowering of the British tax on tea. This seemingly beneficial act was regarded as sinister because the 100 per cent tax at the time had inspired a thriving underground business that smuggled in tea from The Netherlands to avoid paying tax. If the tax were lowered, it would make legal imports more attractive and drive out local business.

“The fear was that a tax would push out smugglers and the [British-backed] East India Company would come in and be granted a monopoly over the tea trade. And once the principle of taxation was accepted, then taxes could be raised again in future. This led to the idea of no taxation without representation,” he said.

Philip Dawe, The Bostonian’s Paying the Excise-man, or Tarring & Feathering, London, 1774.

![]() The tea boycott was symbolic but stupid. They were just depriving themselves of the tea that they owned. People moved to more satisfying symbols of protest, but the idea of tea as a symbol has endured.

The tea boycott was symbolic but stupid. They were just depriving themselves of the tea that they owned. People moved to more satisfying symbols of protest, but the idea of tea as a symbol has endured. ![]()

Dr James Fichter

The British over-react

Parliament responded to the Boston Tea Party with the Coercive Acts, which closed the entire Boston port as punishment. It was an over-reaction to a protest that, as Adams’ actions showed, was not so fully embraced by the colonists, but it added fuel to the patriots’ fire and led directly to the Continental Congress.

“The tea boycott was symbolic but stupid. They were just depriving themselves of the tea that they owned. People moved to more satisfying symbols of protest, but the idea of tea as a symbol has endured,” Dr Fichter said.

Much of Dr Fichter’s research looks at tea in the wider society, where he found newspapers of the day carrying tea advertisements while in the same editions running editorials that advocated a boycott of tea. Propaganda was put out that tea would, among other things, cause stillbirths. It was also “vaguely genderised,” he said, with women portrayed as weak-willed in controlling their tea drinking, leaving it up to the men to be firm in their resolve.

Symbolic burnings of tea could be half-hearted or have ulterior motives. One tea importer whose ship was burned in part at the urging of rival merchants was forced to publish a declaration that he had burned the ship of his free will. Meanwhile, his rivals continued to sell their own tea to American revolutionaries. In a separate case, a shipment of smuggled tea landed near a small town in New Jersey and patriots seized and burnt it. One patriot, however, was caught with sacks of tea in his pants – he had joined in to get free tea. The man was a neighbour of the patriots and the case was laughed off.

Higher expectations

Despite these stories, “the British response to the Boston Tea Party was ridiculously over the top,” Dr Fichter said. “This was a private

matter – the East India Company’s property was destroyed. Why involve the government in punishing a whole population? But Parliament’s attitude was that these people needed to obey.”

One question that interested him was why the 13 American colonies protested and other nearby British colonies did not. Present-day Canada stayed out because the French population had been promised freedom of religion after Britain defeated France there in 1763. Jamaican colonists needed military protection from restless slaves. Neither place saw an urgent need for change.

“The patriots had higher expectations because Britain was the freest society at the time. By comparison, there was more cause to protest among the Spanish or French colonists. And Russian peasants didn’t have any expectations so they didn’t rise up,” he said.

The tea boycott itself was short-lived. By the end of 1775, people were openly consuming tea more or less as before. Thomas Jefferson was even served tea while he wrote the Declaration of Independence in 1776. But the myth of tea as a symbol of protest has endured.

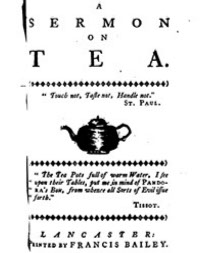

Though not actually a sermon, this piece of anti-tea propaganda was printed in both South Carolina and Pennsylvania in 1774.

Tea advertisements from Alexander Gillon (top, from South Carolina Gazette, November 29, 1773) and Samuel Gordon (bottom, from South Carolina Gazette,

November 1, 1773).