Scientists have long questioned the connection between global warming and El Niño. Some studies suggested that global warming would make El Niño more extreme, others that there would be no change, and yet others even less extreme. “In short,” says Dr Li Jinbao of the Department of Geography, “there was a lot of confusion!”

Dr Li has now dispelled that confusion by leading an international research team in a study of tree rings which found that El Niño has been aggravated by global warming, and as a result we can expect more extreme weather conditions in years to come.

Our findings provide crucial constraints for improving climate models, and will lead to more accurate predictions on future extreme climate conditions.

Dr Li JinbaoFloods and droughts

Since El Niño has a significant effect on weather in the Pearl River Delta, these extremes, including floods and droughts, will affect Hong Kong directly, so the findings have great implications for the city’s long-term water resource management.

Indeed, those extremes have already begun. “The 1990s saw a great deal of extreme weather,” says Dr Li. “The decade of 2000s seemed less extreme, but the most recent few years see a new upsurge. Indications are that the general trend is upward ever since the beginning of 20ᵗʰ century.”

The study involved the analysis of more than 2,200 tree-ring chronologies from Asia, New Zealand, and North and South America, and was the first to cover such a large area and to include trees up to 700 years old from the tropics. Instrumental records on El Niño only date back about 150 years, not long enough to ascertain if they have been affected by global warming. Dr Li’s study shows that tree rings can provide that opportunity.

El Niño and La Niña, the unusual warming and cooling that occurs in the tropical Pacific every two to seven years, spark severe weather worldwide. Their activity can be ascertained through tree rings because, basically, El Niño prompts warm surface temperatures in the eastern Pacific, which in turn gives rise to unusually wet winters in regions like southwest North America. The wetter the winter, the wider the tree ring.

“As a team we achieved two things: first, putting together data from all around the Pacific, in particular the tropical regions; and second, including data over such a long time period,” says Dr Li. “Usually tropical trees die young, only living a couple of hundred years or so as they can’t survive too long in such wet conditions. But our researchers headed to very remote, dry regions in the tropics – such as the South American Altiplano where trees like Polylepis taracapacana live much longer.”

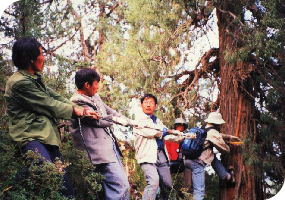

Dr Li Jinbao (centre) and his team take samples from an 800-year-old Qilian juniper

(Juniperus przewalskii) in the Qilian Mountains, northwest China, in 2001.

Dr Li Jinbao (centre) and his team take samples from an 800-year-old Qilian juniper

(Juniperus przewalskii) in the Qilian Mountains, northwest China, in 2001.The methodology is relatively straightforward: using increment borers – equipment which changed little in more than a century – the team collected samples from more than 50,000 trees along the Pacific Rim. It took them more than a decade.

Putting these tree-ring data together, the team found something hitherto unknown about El Niño. “We discovered that recent El Niño activity is at its highest for the past 700 years, possibly a response to global warming,” says Dr Li. Finding the connection also has implications for improving climate models. “There’s been no guidance for improving climate models, and scientists have been struggling to find ways to go about it. Our findings provide crucial constraints for improving climate models, and will lead to more accurate predictions on future extreme climate conditions.”

The team has also discovered large tropical volcanic eruptions could cause worldwide extreme weather through their effects on El Niño

The team has also discovered large tropical volcanic eruptions could cause worldwide extreme weather through their effects on El Niño

Volcanic effects

They also studied the effects of volcanic eruptions on El Niño. “In the year after a large tropical volcanic eruption, our record shows that the east-central tropical Pacific is unusually cool (La Niña), followed by unusual warming (El Niño) one year later. Like greenhouse gases, volcanic aerosols perturb the Earth’s radiation balance. This supports the idea that the unusually high El Niño activity in the late 20ᵗʰ century is a footprint of global warming,” explains Li. “This discovery is very important, because next time there is a large tropical volcanic eruption, we will know what climactic conditions to expect.”

Dr Li says he has been lucky to work with many top scientists in the field, including Professor Xie Shangping (University of California at San Diego) who was his post-doctorate adviser, and Dr Edward R Cook (Columbia), his PhD adviser.

Looking back, Dr Li recalls that as a fresh postgraduate student he wasn’t sure what area of research to pursue. “Climate was not a hot topic as it is today,” he says, “but the thought of doing research in beautiful forests around the world appealed. And then when we realised we could use tree rings to comment on El Niño, it all came together.”■