Language and the construction of stories are at the heart of literature, and also law. But the two are often boxed off from each other: legal scholars and students focus on statutes while those in the arts focus on literature and more recently film.

It’s a shame, says Associate Professor of Law Dr Marco Wan, because there is so much they can learn from each other.

Dr Wan is among those trying to build a bridge between the two by pursuing research in areas where law and the arts intersect. He is also helping to teach the new double degree in Law and Literary Studies, launched by the Faculties of Law and Arts in 2011 to provide students with a firm foundation in both fields.

“Within the Faculty of Law there is this realisation that we need to move beyond seeing the law as rules and doctrines, and really get a different perspective on the law as a linguistic product and part of cultural and historical heritage,” he said.

“There are a lot of commonalities between literature and the law. A literary critic working on a novel and a barrister arguing a case in a trial seem to be doing very different things but at the end of the day they are both working with language and narrative. Law has a lot to learn from literature and vice versa.”

Reflecting the legal concerns of the day

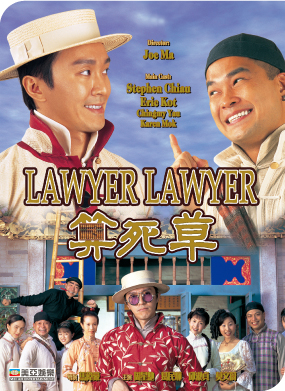

Dr Wan looks into the connections between law and the arts in modern-day Hong Kong by studying legal-related Hong Kong films from 1984 to 1997 including Lawyer, Lawyer (1997).

Dr Wan looks into the connections between law and the arts in modern-day Hong Kong by studying legal-related Hong Kong films from 1984 to 1997 including Lawyer, Lawyer (1997).(Courtesy of Mei Ah Entertainment)

These commonalities were recognised in Shakespeare’s time when some of his plays were performed in the Inns of Court in London. Legal problems and questions were also incorporated into literature, for example, in The Merchant of Venice which considers whether law or equity is best suited to achieving justice.

Dr Wan is seeking to bring a similar awareness of the connections and mutual influences between law and the arts to modern-day Hong Kong. In one study, he looked at Hong Kong films with a legal theme from 1984 to 1997, straddling the Joint Declaration and the handover. The films ranged from 1985’s The Unwritten Law with Andy Lau Tak-wah to 1997’s Lawyer, Lawyer with Stephen Chiau Sing-chi.

“In the period leading up to the handover, the law was very much on the minds of Hong Kong people,” he said. “You had the drafting of the Basic Law, concerns about human rights after Tiananmen Square Incident, the drafting of the Bill of Rights, the choice of Chief Justice, and the creation of the Court of Final Appeal.

“Films reflected people’s anxieties about the law at the time and they gave us something we can’t get in formal legal history textbooks, which are interpretations of events and facts. They gave us a sense of what it was like living in that period, of lived experience.”

You’re used to thinking of a discipline in a set way, then suddenly it’s like a kaleidoscope. You shift the lens and see all these different patterns.

Dr Marco WanA kaleidoscopic view

Dr Marco Wan compares the lawsuit faced by Ai Weiwei, an outspoken Mainland artist who was arrested ostensibly for tax evasion in 2011, to that of Oscar Wilde, an Irish playwright who was prosecuted for his ‘trial for gross indecency’ with other men in his time.

Dr Marco Wan compares the lawsuit faced by Ai Weiwei, an outspoken Mainland artist who was arrested ostensibly for tax evasion in 2011, to that of Oscar Wilde, an Irish playwright who was prosecuted for his ‘trial for gross indecency’ with other men in his time.

Dr Wan has also looked at instances where law and literature intersect more directly. He recently completed a manuscript on the literary trials of the 19ᵗʰ century, including that of Gustave Flaubert who was charged with obscenity for Madame Bovary. Dr Wan showed how the densely metaphorical language of the cross-examination was used to support the charges against Flaubert.

He has also compared the situations of Mainland artist Ai Weiwei and Irish playwright Oscar Wilde, who both encountered trouble with the law. Mr Ai was arrested ostensibly for tax evasion in 2011 but had also riled Mainland authorities with statements and artistic works critical of the government. Mr Wilde was tried for sodomy which affronted the Victorian morals of his time. Dr Wan draws a connection between the two.

“I’m interested in the fact they are both transgressive figures and transgression almost always brings people into contact with the law. I think transgression is an interesting concept – it’s not necessarily a bad thing, it’s often done by people who see things differently or see beyond the horizon of what a society considers acceptable or normal,” he said.

In a sense, that is what the combination of law and literary studies aims to do. The goal is to get students to see beyond the laws and statutes and understand a situation in all its human complexity.

“It’s a shift of perspective. You’re used to thinking of a discipline in a set way, then suddenly it’s like a kaleidoscope. You shift the lens and see all these different patterns. You can always come back to the first point but your perspective will be enhanced,” he said.■