The more things change, the more they remain the same, as Dr Carol Tsang of the Department of History has discovered. Her area of research is women’s health and reproduction in Hong Kong and China, and her female students and acquaintances keep reminding her that while they have plenty of opportunities in career and education, in the home, not much has changed.

“I have met a lot of women from different walks of life who feel the social expectations of marriage and motherhood limit their capacity. They feel pressured to get married by a certain age and to have children, especially a male heir. And after having children and marriage, they feel their careers stall. These social expectations haven’t changed much over the decades,” she said, as her 15 years of research has shown.

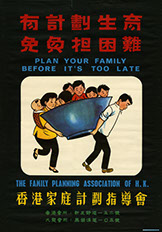

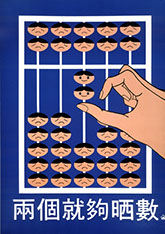

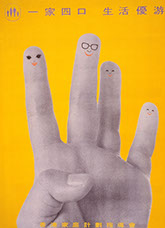

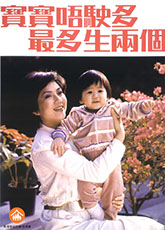

Dr Tsang’s first major project was a history of the Family Planning Association of Hong Kong (FPAHK), an organisation founded in 1950 to promote birth control to ordinary Chinese families in the context of traditional values. The Government wanted to contain population growth and the FPAHK supported that goal through promotions such as the ‘Two is Enough’ campaign featuring a smiling family with just two children – the message being that birth control was a path to a cordial family life.

“What interested me was how the FPAHK and the Government used Chinese family values to promote birth control. This was totally different from Europe and America where birth control was tied closely with the women’s movement and sexual liberation. In Hong Kong, it was about Chinese values and being an ideal Chinese nuclear family,” she said.

![]() What interested me was how the

What interested me was how the

Family Planning Association of Hong Kong and the Government used Chinese family values to promote birth control. This was totally different from Europe and America where birth control was tied closely with

the women’s movement and sexual

liberation. ![]()

Dr Carol Tsang

Colourful debate

Birth control was a more contentious topic in the pre-war era. American Margaret Sanger, an activist for birth control who was popular in China, was invited to Hong Kong in 1936, where she gave a talk on such methods as sterilisation and the diaphragm. Non-Catholic Christians welcomed her message because they thought birth control could help ordinary people and deter abortion, but there was strong opposition from Catholics.

“It was a very colourful debate. Hong Kong people were pretty split in terms of accepting or rejecting artificial birth control, but at the same time, many were already practising it by taking different patented medicines or visiting Chinese abortionists,” Dr Tsang said. The talk had a lasting effect, though: the FPAHK links its heritage to Sanger’s visit because she inspired the establishment of FPAHK’s predecessor, the Hong Kong Eugenics League.

Abortion was an accepted form of birth control within Chinese society, especially in the chaotic period before the Second World War but, as today, it exposed rifts in society. The Government was keen to curtail abortionists, many of whom came from Mainland China and were regarded as charlatans by officials, and it wanted to establish the legitimacy of Western midwifery. “A lot of hidden stories in reproduction show clashes between Western and Chinese practitioners,” Dr Tsang said.

Women’s voices in these debates were often muted. In the first half of the 20th century, for instance, there were numerous newspaper articles and advertisements on women’s fertility, but they were written with male readers in mind as most women were illiterate.

Same discourses today

“Some of the advertisements were presented

as stories. There was one that featured a man who didn’t have a male heir, but after buying a patented medicine for his wife, she gave birth

to a son. Their success and happiness were said to be due to this medicine,” she said. She sees echoes of that thinking today in television commercials for medicines to restore health

that are set against images of a happy family.

“It surprises me that 100 years on, we still use the same discourses to market these things. It may be repackaged as modern science today, but in the early 20th century it was also packaged as science.”

Dr Tsang brings these insights to the classroom, too, where she teaches the global history of reproduction and birth control and Common Core courses on women’s roles across time and culture, motherhood in China, and masculinity studies. The latter includes discussions on the role of men in the history of gender, reproduction and birth, an area that has been neglected in much scholarship and which will be a focus of her research moving forward.

In the meantime, Dr Tsang has a more pressing and pertinent task, having recently given birth to her first child, a girl. “People ask me if it’s a first child and when I tell them it’s a girl, they ask, so do you want a boy for the second child? It’s affirming what I read in history,” she said.

Next

Back

An advertorial portraying a happy family in which the

wife gave birth to a son after taking a patented

medicine published on Wah Kiu Yat Po in March

1926.

BIRTHING IN HONG KONG

Colonialism and modernisation have both brought changes to reproduction and birth control practices in Hong Kong. But some attitudes are proving to be immutable.

Posters promoting birth control and family planning by the Family Planning Association of Hong Kong from the 1950s to 2010s.

Home

May 2019

Volume 20

No. 2

Cover Story