The Cultural Revolution has been written about by countless scholars, who have picked apart a period that seemed both chaotic and organised– of Little Red Book-waving Red Guards running amok, destroying the old and denouncing counter-revolutionaries, and of labyrinthine backroom politics with Mao at the centre. But if anyone can shed new light on the period, it is Chair Professor of Humanities Frank Dikötter.

Professor Dikötter’s two previous books, Mao’s Great Famine and The Tragedy of Liberation, drew extensively on Party archives that were newly-opened in the late 1990s and contained reports that the Central Government had otherwise kept out of view. He unveiled cruel directives, such as killing quotas, an official disregard for lives lost, and the impacts on ordinary Chinese.

He returned to these sources for his latest book– albeit probably for the last time because the Government has started to pull down the shutters on its archives – and has again lifted a veil on a period that many might have thought was exhausted of new insights.

“There are books and books written about the ‘court politics’ of the time, some of them very good, others not so convincing, but in the end very few have anything to say about what the Cultural Revolution actually meant to people of all walks of life,” he said.

His narrative starts with the aftermath of the failed Great Leap Forward of 1958–1961, which killed at least 45 million people and left Mao in a precarious position. Mao was determined to protect his position and his legacy and by 1966 he was ready to move – or at least, to get others to move for him.

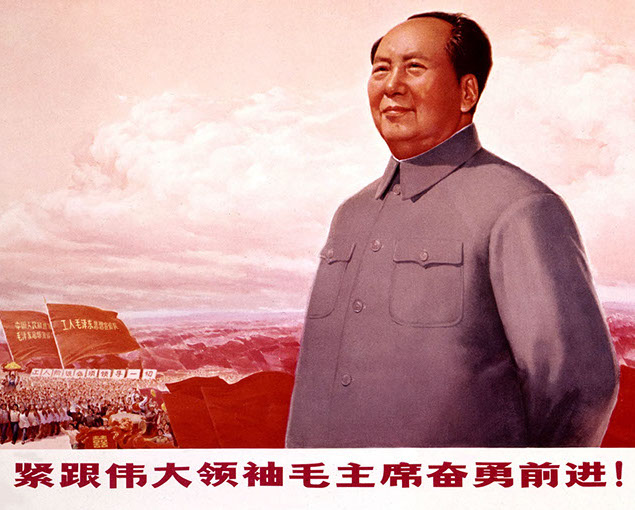

![]() The punchline is, the people are as usual far ahead of their own government. The people are the true architects of economic reforms, not Deng Xiaoping.

The punchline is, the people are as usual far ahead of their own government. The people are the true architects of economic reforms, not Deng Xiaoping. ![]()

Professor Frank Dikötter

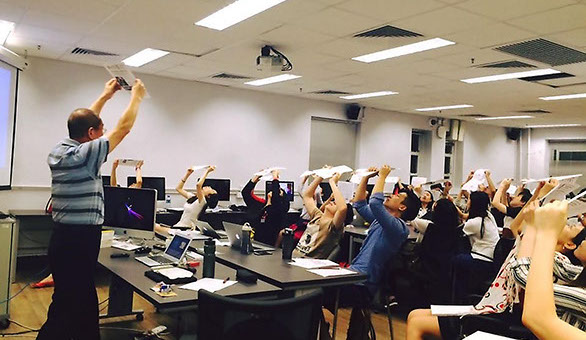

![]() Students are challenged to sort out the truth from the propaganda and work out which materials are valuable.

Students are challenged to sort out the truth from the propaganda and work out which materials are valuable. ![]()

Mr Qian Gang

This turmoil was followed by the ‘black years’ of 1968–1971 when a military dictatorship restored order. Soldiers fanned out to factories, schools, government units and other areas of daily life. Purges affected up to one in 50 ordinary people. The planned economy, which in the countryside had been relaxed during the red years, came back with a vengeance.

But none of that sufficiently soothed Mao’s paranoia about his legacy. He turned against the military, which was allied with Mao’s number two Lin Biao, who died mysteriously in a plane crash in 1971. The internal chaos in the Communist Party that ensued led to a period that Professor Dikötter calls the ‘grey years’, from 1971 to 1976.

Here is where Professor Dikötter’s archival work is revelatory. He found reports compiled by the Party’s own investigators that revealed the Cultural Revolution was failing in its aims – it was not overturning the old culture or capitalism, but quite the opposite.

“The Cultural Revolution started off as an attack against the Party itself, unleashed by the Chairman himself. Now that the army is gone, ordinary people realise that the Cultural Revolution has badly damaged the organisation of the Party, that Party members no longer have the clout they once had.”

Returning to the scene

Qian Gang said that studying the birthday papers enabled the students to “return to the scene and to seek historical evidence, truth and interest in the written record of the time. Students are challenged to sort out the truth from the propaganda and work out which materials are valuable. Through this method, they learn how to turn journalism history into personal narratives. In the end, they get a better idea of the context around important historical points.”

Students felt the project gave them a better idea of the ongoing power struggles within the Communist Party, foreign policy issues and how disasters such as the Great Famine of 1960–1961 occurred. The papers also revealed much about how people suffered through the Cultural Revolution. Some of the students wrote about actors and actresses who were purged for their involvement in the arts.

The Birthday Papers Project has also attracted press attention within Hong Kong, gaining coverage in several local papers.

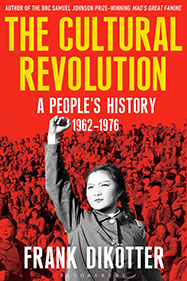

A group of Chinese children in uniform holding Mao Zedong’s ‘Little Red Book’ during China’s Cultural Revolution.

The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History, 1962–1976 is published by Bloomsbury.

Mr Qian Gang teaching students how to ‘read newspapers’ in a different way during one of his classes.

Reimagined in a class exercise – tweets from Mao: “I’m a Party member and I’m a citizen. You [referring to Deng Xiaoping] don’t allow me to participate in the Party conference and that is a violation of Party rules. You [referring to

Liu Shaoqi] don’t allow me to speak and that is a violation of the Constitution.”

Back

CHINA’S

COLOUR REVOLUTION

Having autopsied the early years of Communist Party rule and the Great Leap Forward to much acclaim, historian Frank Dikötter has now turned his sights on the Cultural Revolution – a period he divides into ‘red’, ‘black’ and ‘grey’ years and where, surprisingly, he finds the seeds of China’s economic reforms. Meanwhile, journalism students have been gaining insights into this period in Chinese history by studying newpapers from the time.

Propaganda poster from the period of the Cultural Revolution.

One thing after another

At Mao’s urging, the Red Guards rose up in 1966–1967 – what Professor Dikötter calls the ‘red years’ of the Cultural Revolution, when students attacked teachers and ordinary people attacked Party members. “These are the years of willed chaos, where the Chairman uses the people at large to unsettle Party members, including his close colleagues in the higher echelons of power,” he said.

Professor Frank Dikötter’s division of

the Cultural Revolution

Red years

1966 - 1967

Black years

1968 - 1971

Grey years

1971 - 1976

People take things into their own hands

And so they embark on a ‘silent revolution’, in which whole villages turn capitalist by setting up markets and trading on the black market. “This was the biggest discovery of the archives,” he said. “The pretence of the collective economy is maintained because farmers give a share of their private crop to the local cadres who can then deliver what they have to deliver to the State. They keep the State off their back.”

All of this happened some years before Deng Xiaoping came to power and heralded economic reforms – it was even starting to happen during the Cultural Revolution, when there was a thriving black market in aluminium badges of Mao. “The punchline is, the people are as usual far ahead of their own government. The people are the true architects of economic reforms, not Deng Xiaoping,” Professor Dikötter said.

Historic perspective

If Twitter had been around during the Cultural Revolution, what would Chairman Mao have tweeted? A project by the Journalism and Media Studies Centre seeks to provide an answer.

Fifty years after the start of China’s Cultural Revolution, students and alumni of the Journalism and Media Studies Centre (JMSC) found new angles and insight into the historic event when they compiled new articles based on the original reporting in papers dating back to their parents’ birth dates.

Director of the JMSC’s China Media Project Mr Qian Gang said the thinking behind the exercise was to give students insight into the lives and socio-economic conditions in China as it would have been experienced by their forbears. The ‘Birthday Papers Project’ began as a class assignment for which students were asked to research news reports which were published on the day their parents were born and to use them as a basis for analysis of the historical period.

Such was the interest in the assignment that it grew into a full-blown project, drawing information not only from national and local newspapers but also on video and audio recordings from the time. Qian Gang also teaches at Peking University Shenzhen Graduate School, and his students there did a Birthday Papers Project too. Some contributors have even travelled back to their hometowns to search the archives of local newspapers.

The JMSC students have been producing two or three of these ‘newspapers’ a week since January. The first ones focussed on events leading up to the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, which began on May 16, 1966, with a public notification from Chairman Mao Zedong warning the country that enemies of communism had infiltrated the Party and needed to be purged.

One paper that received a lot of attention was written by Master of Journalism student Lei Feifei, who considered what Mao might have ‘tweeted’ in the run-up to and during the Cultural Revolution. Her imagined tweets included: “I’m a Party member and I’m a citizen. You [referring to Deng Xiaping] don’t allow me to participate in the Party conference and that is a violation of Party rules. You [referring to Liu Shaoqi] don’t allow me to speak and that is a violation of the Constitution.”

References and links to Lei Feifei’s article appeared briefly on social media inside Mainland China, but have since been removed by government censors.

In that sense, the Cultural Revolution was a period of transition from the experimentation and terrible collectivisation failures of the first 17 years under Communist rule, to the market-oriented economy that persists today. But it has also left a darker legacy, he said: “As ordinary people were able to wrench basic economic freedoms away from the State, the Party became even more determined to repress their political aspirations.”

Having pulled the roots of modern China into the light, Professor Dikötter’s next project is to look at how dictators, such as Mao, Hitler, Stalin and Kim Il Sung, forge their image and build up a cult of personality. “You cannot truly understand the machinery of repression without looking at the cult of personality. They go hand in hand,” he said.