After The Split

The psychological and social impacts of divorce linger long after the final papers have been signed, as the Director of the Hong Kong Jockey Club Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention Professor Paul Yip Siu-fai explains.

No one wants to stay in an abusive marriage, or even a simply unhappy one, but disentangling from such a situation can come at a personal and social cost, as research by Professor Paul Yip Siu-fai and his team has shown.

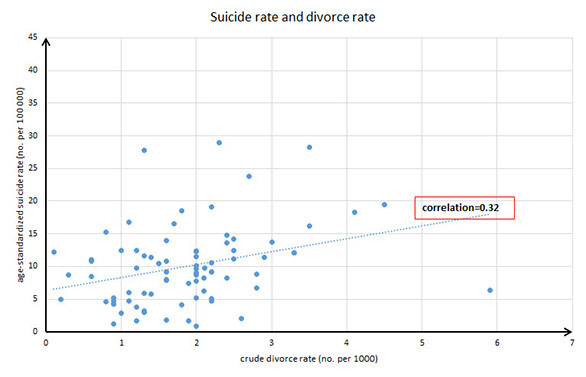

Starting with the worst outcome, they have found that divorce increases the risk of suicide based on a meta-analysis of studies of divorce in 11 countries in Europe, North America, Australia and Asia that took into account culture and gender.

“Across populations, it doesn’t matter if it is East or West, the suicide rate is higher among the divorced compared to the married,” he said, “and it seems to have a higher impact in collective societies like Korea, Japan and Hong Kong. Unlike in Western countries where divorce seems to be quite acceptable, there is a stigma that you’re a failure, you can’t hold your marriage together, and so on.”

On average, divorced men were found to be 3.49 times more at risk of suicide and divorced women 3.15 times more at risk. But among Asian men, the risk ranged from 4.81 in Japan to 5.90 in Taiwan, with Hong Kong coming near the top at 5.80. Among Asian women it ranged from a very low 1.96 in Japan to 8.00 in Korea where child custody used to be granted to the father; the ratio for Hong Kong women was 4.30.

The suicide risk may also filter down to the next generation. Professor Yip is Chairman of a Hong Kong government committee looking at student suicides and in at least half the cases studied, the students came from broken families or homes with serious family strife.

![]() If the marriage is beyond repair, there

If the marriage is beyond repair, there

is no point in having an unhappy marriage, but they should try to make it a happy divorce. ![]()

Professor Paul Yip Siu-fai

Poverty risk, too

But suicide is not the only effect. Divorce also increases the poverty risk and with that, the demand on government welfare services. While about 14.5 per cent of Hong Kong households live below the poverty level, including government subsidies and other assistance, among single divorced parents the rate is 30 per cent.

Moreover, the city’s tough housing conditions mean divorced couples can be forced into complex and difficult situations when it comes to finding somewhere to live. Half the population lives in subsidised housing and cannot afford the high costs in the private market.

“Sometimes even after divorce, couples are forced to stay together in public housing for the interim because there is nowhere else to stay. Of course it’s not ideal. If they can stay happy together, then why would they have divorced?” he said. “But domestic violence is not that uncommon and tragedies do occur.”

All of that is not to say divorce is bad in general. “It can be a good thing for individuals, especially if there is an abusive spouse. It used to be that Asian women in particular would swallow problems for the family or were not financially independent, so they had to stay. Nowadays women are better educated and more independent. But at the population level divorce is not such a good thing as family support is weakening in the community,” he said.

How to ease the pressure

Professor Yip believes the Government and other institutions could help ease the pressures by providing more support for families going through divorce. Children should be protected, particularly from being used by their parents in divorce proceedings. Schools should work at de-stigmatising divorce so children don’t feel discriminated against, and they should be more sensitive to the rapid changes in family structures – about 23,000 couples divorce each year and about one-third of marriages are remarriages.

“When people talk of student suicide, they tend to mention academic pressure, but actually academic pressure doesn’t directly link to suicide – otherwise the situation would be much worse. However, it does seem that social support can be weak for divorced families or remarried families,” he said, adding: “We need to enhance resilience and induce hope to our young people.”

“If the marriage is beyond repair, there is no point in having an unhappy marriage, but they should try to make it a happy divorce.”

Professor Yip also believes more should be done to address some of the causes of divorce. Long working hours and long separations due to the need to travel for work are not conducive to family life. Short-term work contracts also create unstable conditions for starting and maintaining a family.

But he stops short of advocating policies to encourage marriage, pointing to Singapore where the divorce rate has risen steadily despite inducements such as priority for married couples in housing allocation. Hong Kong’s divorce rate in contrast has levelled off as people delay marriage until they are older. “In our studies, we have found that the older you marry, the less the chance of divorce,” he said.

Back

The correlation between the age-standardised suicide rate and the crude divorce rate.