The term ’Lion Rock spirit’ originated from a television show called Below the Lion Rock, which often illustrated the preseverance and solidarity of Hong Kong’s working class in the 1970s.

BEYOND THE LION ROCK

Hong Kong popular culture had a brilliant flowering in the last decades of the 20th century, but has since wilted, overtaken by cultural imports from Korea, Japan, Taiwan and the Mainland. Two scholars of Hong Kong culture consider its past, present and future.

Step back 30 years ago and Hong Kong-made music, films and television programmes were everywhere. They topped sales and viewership figures not only in Hong Kong but in Chinese-speaking communities around the world. Even Hollywood came knocking.

To cultural critics like Dr Ng Chun-hung of the Department of Sociology, this was more than an entertainment phenomenon. The brash, pragmatic, heartfelt values conveyed in the songs and storylines were the embodiment and touchstone of modern Hong Kong identity. They helped to shape the city’s idea of itself.

“If you look at other places, ideas of national identity are developed and promoted by government or intellectual sources. But in Hong Kong these sources were silent or absent for many years. Hong Kong did not have a proper government so to speak, it just had a colonial government, and there wasn’t a big intellectual circle. So people turned to pop culture stars to feed their imagination. Pop culture was the accidental hero articulating the Hong Kong story.”

The rise of that culture is generally considered to have started in 1974 – the year HKU graduate and pop singer Sam Hui and his brother Michael Hui released their seminal film, Games Gamblers Play. Its fast-paced depiction of clever amoral people who got what they wanted, peppered with lots of gags and structured around a loose plot, was a huge hit. Around this time Sam also started singing in Cantonese instead of English and Mandarin, and television shows like Radio Television Hong Kong (RTHK)’s Below the Lion Rock focussed on life in post-war Hong Kong. “This was a new era. The stories being told were not about China, but about Hong Kong,” Dr Ng said.

But that was then and this is now. Hong Kong popular culture is a weak presence even here in Hong Kong. Is it on its last legs? Dr Ng and Professor Stephen YW Chu, who heads the Hong Kong Studies programme in the Faculty of Arts, are among scholars who have been studying its future prospects, and also just how it helped to shape the identity of Hong Kong.

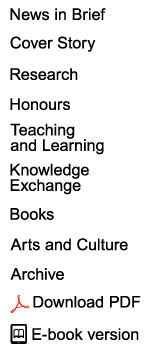

One of Dr Ng’s projects is ’James Wong Stories: Sky over Sham Shui Po 1949–1960’, a website featuring James Wong, a renowned Cantopop lyricist and an icon of Hong Kong popular culture.

James Wong was a recognised Cantopop lyricist and writer.

![]() If you look at other places, ideas of national identity are developed and promoted by government or intellectual sources. But in Hong Kong these sources were silent or absent for many years… Pop culture was the accidental hero articulating the Hong Kong story.

If you look at other places, ideas of national identity are developed and promoted by government or intellectual sources. But in Hong Kong these sources were silent or absent for many years… Pop culture was the accidental hero articulating the Hong Kong story. ![]()

Dr Ng Chun-hung

Articulating an identity

“The best starting point to look at Hong Kong identity is to examine the time when Hong Kong did not have an identity,” said Dr Ng. Before 1950, the city was a small settlement at the base of China, with a highly transient population occupied with trade and small-scale manufacturing. It was hardly a place to get attached to. Then more than a million refugees arrived from revolutionary China and everything changed.

For the first time Hong Kong had a large stable population. A baby boom ensued – in 1966, 40 per cent of the population was under age 14 and almost all of those youths were born in Hong Kong. An economic boom brought rising prosperity. And local political developments heightened people’s sense of a shared origin and future. While the 1966 and 1967 riots left many youth in particular disillusioned with Mainland politics, the policies of Governor Murray MacLehose in the 1970s – such as expanded housing, education and welfare programmes and recognition of Cantonese as Hong Kong’s second official language – strengthened the sense of Hong Kong as home.

All that was lacking was an articulation of that feeling and what it meant to live and grow up in Hong Kong. This was where popular culture came in, Dr Ng said.

“A main ingredient of identity is the stories circulating in a population. Pop culture became an important source of these stories and it depicted some of the core features of Hong Kong identity: being quick-thinking, being smart – I earn more money than my neighbour in China – and taking pride in being pragmatic and efficient. All of that was a big part of the Hong Kong identity.

“There was also another set of values that are integral to a refugee society. Hong Kong started as a refugee society in the 1950s and there was a memory of that in a big chunk of the population – you could be rich today but very poor tomorrow. So a second strand of Hong Kong identity lay in the need to help your neighbour and be moral instead of money-oriented. Some pop culture products worked in the idea of a hero saving a poor community, which harks back to traditional Chinese fiction and folk stories.”

These values were reflected in programmes such as the sitcom Casanova ’73 which aired in 1973 and showed families experiencing and laughing about real-life issues such as corruption, and in films like Games Gamblers Play. It was also conveyed by pop stars such as the ‘Four Heavenly Kings’ – singers Andy Lau, Jacky Cheung, Aaron Kwok and Leon Lai – who crossed over into television and film and reinforced the messages across mediums.

![]() This is a very strange phenomenon.

This is a very strange phenomenon.

The younger generation has a heightened sense of local belonging, but they are

not consuming Cantonese pop culture

any more. ![]()

Professor Stephen YW Chu

Lost in transition

From the 1990s, though, sassy Hong Kong culture started to lose its bloom under political, economic and demographic pressures – the rise of China, 1997, globalisation, and the desire of every new generation to remake the world in their own way. The old cultural products became passé, as comments by Professor Chu’s students illustrated. “They told me that anyone who is a Cantopop singer and at the same time a TVB (Television Broadcasts Limited) actor [a formula for huge success in the past] only appeals to middle-aged housewives,” he said.

Professor Chu’s Lost in Transition: Hong Kong Culture in the Age of China was published in 2013. He is now working on a sequel that explores the new possibilities of Hong Kong culture.

Professor Chu is author of Lost in Transition: Hong Kong Culture in the Age of China, which was published in 2013. It is easy to say Hong Kong culture was swamped by China, he said, but in his area of specialty, Cantopop music, Korean and Japanese pop music are even more popular than Mandarin pop music (which is mostly from Taiwan). Industry response has also been a factor in the decline. For example, Hong Kong was the only open market for Chinese pop music in the 1970s and 1980s but the industry failed to act when Mandarin pop started gaining popularity in the 1990s. “The industry should have diversified the music and fan base, but all it did was sik law boon – eat up the assets. Young workers tell me it has been impossible to overhaul the Cantopop industry because senior people are close-minded,” Professor Chu said.

“Television and cinema have seen a similar decline. The cultural industries have lost their creative synergy.”

Local filmmakers entered into co-productions with Mainland partners so they could reach the huge audience there, while singers and actors sought work there – quite a different situation from the pre-2000 period when going to the Mainland was seen a sign of having failed to make it in Hong Kong.

In terms of popular culture’s impact on identity, 2003 may have been the culmination of all these other forces taking shape, Dr Ng said. The huge protest on July 1 helped to waken people’s consciousness and also led the Government to be more vocal about Hong Kong’s relationship with China and the need to support such things as national education. Intellectuals also grew in number and spoke out. “These other agents became more active in articulating Hong Kong identity. Pop culture declined as a force that shapes identity, as well as economically,” he said.

But that force, while weaker, has not disappeared. Hong Kong audiences never really warmed to the Mainland co-production films, which appeased censors by avoiding topics that had been hallmarks of Hong Kong cinema, such as triads and ghost stories. Around 2009, several filmmakers began making movies that looked wistfully on Hong Kong’s recent past, such as Echoes of the Rainbow and Gallants. “On the one hand these films are a nostalgic imagination of the good old days of Hong Kong and on the other hand, they use the past as a source of their imagination for a better future for Hong Kong,” Professor Chu said.

That longing for the past does not extend to the actual pop culture of that period, though. “This is a very strange phenomenon. The younger generation has a heightened sense of local belonging, but they are not consuming Cantonese pop culture any more,” said Professor Chu. So where does that leave the culture that helped to define a generation?

_e-crop-u13171.jpg)

HKU alumnus and Hong Kong’s leading and award-winning lyricist Lin Xi (left) at the talk ’The Hong Kong I Love’.

Still, we’ve come a long way

Dr Ng sees a different role emerging. “Pop culture has not died out. People are resurrecting some of the older links. For example, Below the Lion Rock used to be hated by the generation born in the 1980s and 1990s because they thought it was about old Hong Kong – it talks about sharing the same boat and having to work hard and so on. But after the Umbrella Movement, people injected new meanings into those old words. That song has been in the popular conscience for so long that it is a very good carrier for people to inject a new spirit.

“Hong Kong culture will continue to change. What was done before cannot be erased. Plus the new generation is looking at Hong Kong and saying, I love Hong Kong, I am a Hongkonger, what are some of the things we need to keep hold of? Some of them are using pop culture to reinvent things and to laugh at the Government or media.” He even thinks Hong Kong culture could strengthen as 2047 approaches, provided it remains structurally distinct from Mainland China.

Professor Chu’s Hong Kong Studies programme, the only one in Hong Kong, also illustrates the desire to deepen understanding and connect to Hong Kong’s uniqueness. The course was founded in 2012 to look at the city from a multidisciplinary perspective after it was noticed Hong Kong-coded courses were attracting growing numbers of students. Its introductory course attracts 60 to 70 students a year, though few choose it as a major – a reflection of the enduring practical Hong Kong spirit.

“Their parents say, you are born here, why do you have to study Hong Kong? There is a prejudice that Hong Kong culture is informal, that it’s ‘just’ pop culture,” Professor Chu said. He worries this could worsen if Putonghua takes hold as the language of education. “But I still have hope,” he added. “There weren’t any courses on Hong Kong culture when I was a student in the 1980s, and in the early 1970s Cantopop was considered a subordinate genre.” He is now considering future directions for Hong Kong culture in a sequel to Lost in Transition, tentatively titled Found in Transition.

Dr Ng also thinks perspective helps. “My generation started off badly. People had no place to live, they had nothing to eat. We’ve come a long way. But it is still very sad what has happened in Hong Kong culture in the past 10 or 15 years. It has been tested.”

Hong Kong Studies is an interdisciplinary programme which combines the perspectives of a variety of disciplines, including literature, art history, history, sociology, politics, economics, journalism and communications.

Back