New Application Of

An Old Drug

The discovery that an existing drug can control Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV)-induced tumours in humanised mice may open the fast-lane to a novel therapeutic treatment.

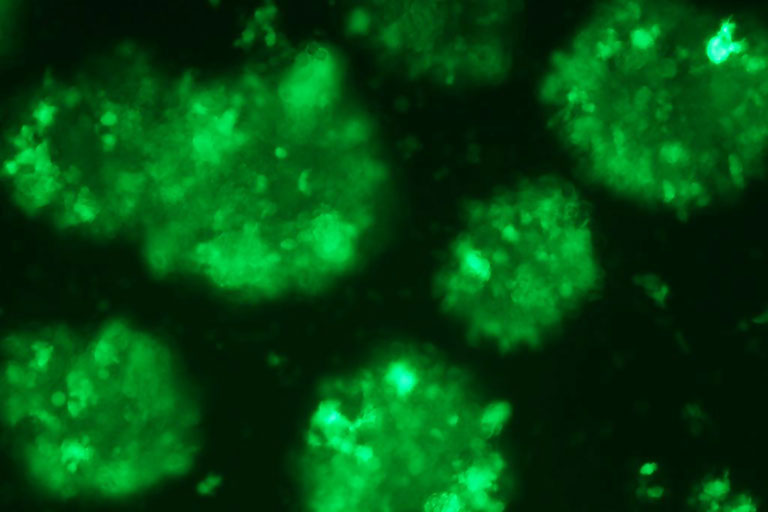

Epstein-Barr Virus lymphoblastoid cells express green fluorescent protein.

![]() As pamidronate has already been used for decades in the treatment of osteoporiasis, this ‘new application of an old drug’ potentially offers a safe and readily available option for the treatment of Epstein-Barr Virus-induced tumours.

As pamidronate has already been used for decades in the treatment of osteoporiasis, this ‘new application of an old drug’ potentially offers a safe and readily available option for the treatment of Epstein-Barr Virus-induced tumours. ![]()

Dr Tu Wenwei

Some 95 per cent of adults have the Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV) present in their bodies. For the vast majority of those, it is latent, and most will never know anything about it. EBV only becomes active when the body is immuno-compromised, but when it does it can lead to EBV tumours and the mortality rate is high.

Current treatment options are limited and far from ideal since side effects are significant. But now an international research team led by Dr Tu Wenwei, Associate Professor in the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, has discovered that an existing drug, pamidronate, which is currently used to treat bone diseases such as osteoporiasis, can control EBV-induced B cell lymphoproliferative disorders (EBV-LPD). The discovery has been published in the prestigious international scientific journal, Cancer Cell.

Epstein-Barr Virus is a herpes virus that latently infects human B cells in most individuals by adulthood. However, effect immuno-compromised patients – for example those who have had an organ transplant – are at high risk of developing EBV tumours such as EBV-LPD. Current treatments destroy all the B cells, not just the infected ones.

“We wanted to identify only EBV-infected cells,” said Dr Tu, “to target the gamma-delta T cells. We thought that if we could use ’forceful energies’ such as pamidronate, then we could enhance the immunity of the gamma-delta T cells.”

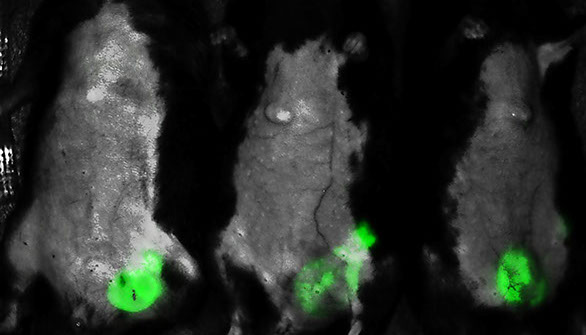

The team established a lethal EBV-LPD model with characteristics mimicking the human disease in humanised mice. They found that pamidronate effectively prevented EBV-LPD development and induced EBV-induced tumour regression in the mice by boosting the immunity of gamma-delta T cells. All the control mice developed solid tumours and nine of 11 control mice died within 60 days, while in the treatment group only two of 10 mice developed solid tumours and nine of 10 mice survived for more than 100 days.

“The discovery has provided the proof-of-principle for a novel immune therapeutic approach, using pamidronate to control EBV-induced tumours by boosting human gamma-delta T cell immunity in the humanised mouse model,” said Dr Tu. More recently, the clinical implication of this new approach has been intensively discussed and highlighted in a commentary published in New England Journal of Medicine, a top clinical medical journal.

The research team at the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine –

(first row from left) Professor Lau Yu-lung, Doris Zimmern Professor in Community Child Health and Chair Professor of Paediatrics; Dr Tu Wenwei, Associate Professor; Professor Godfrey Chan Chi-fung, Tsao Yen-Chow Professor in Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Clinical Professor and Head of the Department;

(second row from left) Dr Liu Yinping, Dr Zheng Jian and Mr Zheng Xiang.

Humanised mice crucial

The use of ‘humanised mice’, which have the complete human immune system, was a crucial element of the research. “We can mimic human diseases in these mice, and see how their human immune cells react to treatment,” said Dr Tu. “EBV cannot infect normal mice cells, so our humanised mice have been vital in linking the gap to enable this research.”

Since returning HKU from Stanford nine years ago, Dr Tu led his team to spend three years establishing the humanised mice in Hong Kong. His laboratory is one of the very few laboratories worldwide to have successfully established this humanised mouse model.

Using humanised mice has also given the team the edge over other biotechnology researchers who are using real mice for their studies. “For them there is a still a big gap between pre-clinical and human trials,” said Dr Tu, “and the transition may not be smooth. Using humanised mice shortens that gap. We expect to start human trials this year, and we want to start quickly as now this research has been published, other medical centres are likely to follow our breakthrough.”

That pamidronate is an existing drug which people have been taking on a long-term basis without problems, gives the team other advantages too. “As pamidronate has already been used for decades in the treatment of osteoporiasis, this ‘new application of an old drug’ potentially offers a safe and readily available option for the treatment of EBV-induced tumours,” said Dr Tu. “Potentially, we can save a lot of money and a lot of time. Usually for a brand new drug, from bench to clinic takes about 10 to 12 years and approximately US$1.5 billion. We expect both the time and the costs to be greatly reduced.”

In addition to an extensive team of experts from the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, the research team also included HKU researchers in anatomy and microbiology and international collaborators from Mainland China and France.

Fluorescent whole body image of mice with Epstein-Barr Virus-induced B cell lymphoproliferative disorders (EBV-LPD), with tumour cells highlighted in green.