THE POST-MORTEM

DILEMMA

To autopsy or not to autopsy? Families increasingly argue against them, but there are good reasons why we need to stem the decline in autopsies, argues pathologist Dr Philip Beh.

When celebrity singer Leslie Cheung jumped off the balcony of the Mandarin Hotel in 2003, Hong Kong went into shock. The media was saturated with stories about the suicide of the beloved entertainer. But after the headlines dwindled, the impact of his death was felt by an unlikely group: pathologists.

Cheung’s family had successfully argued for an autopsy waiver and news reports of this emboldened others to do the same. The coroner of the time was sympathetic and allowed many of the applications.

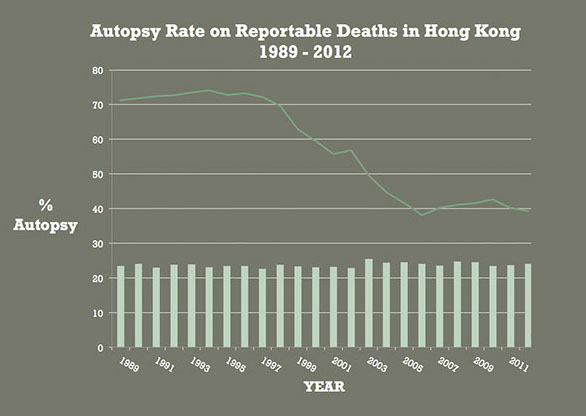

To Dr Philip Beh of the Department of Pathology, this was an outrage. Autopsies are meant to be conducted for 20 reportable incidents, such as murder, suicide and when the cause of death is unknown. Although today’s coroner is less likely to grant waivers, the portion of reportable deaths autopsied has still dropped from 70 per cent two decades ago to less than 40 per cent today.

![]() There are times when we really don’t know what happened. Other than finding out why someone died, could this death have been preventable? Are there unusual deaths we should be aware of?

There are times when we really don’t know what happened. Other than finding out why someone died, could this death have been preventable? Are there unusual deaths we should be aware of? ![]()

Dr Philip Beh

“Families have become much more vocal in challenging the system. In almost 90 per cent of the cases I see now, they ask the coroner to consider waiving the autopsy requirement.

“But there are times when we really don’t know what happened. Other than finding out why someone died, could this death have been preventable? Are there unusual deaths we should be aware of? Here is one scenario. In the earliest days of SARS, when we were hearing news from Guangzhou, a question was raised in the Legislative Council asking what the incidence of ‘atypical pneumonia’ was in Hong Kong. We had no answers because it wasn’t being captured.”

The line graph shows the declining rate of autopsy whereas the bars show the stable percentage of all deaths reported to the coroner.

‘So-called tradition’

Dr Beh has reviewed applications for autopsy waivers over seven years at Queen Mary Hospital and found the reasons were often based on emotion, not fact.

“Most people mentioned so-called tradition. But they are never clear what they mean by that. In general, people don’t like autopsies – this is not unique to the Chinese, the Jewish and Muslim religions don’t like them also.”

Families also cited the old age of the patient, particularly for those who died outside of hospitals such as in nursing homes where there are no doctors on duty to sign death certificates.

“Families will say, what are you doing, they had health problems, they were bed-ridden, in a sense their death is a blessing and now you are creating all these troubles for me. But one of these cases could be a homicide because someone got fed up looking after that person,” he said. “It’s always a dilemma for us how far to push.”

Dr Beh tries to explain to families that it is in their interest to determine the cause of death. If it was an accident, there could be insurance benefits. If they were unhappy with the medical or nursing home care, an autopsy could answer questions. “Surely they want the death to be meaningful, so if anything can be learned, we know about it rather than leaving it dangling in the air.”

He and his team have also been trying to keep bodies intact by using endoscopes to determine the cause of death where possible. Computerised tomography (CT) scans are used in some countries, though not yet in Hong Kong.

In the meantime, Dr Beh has been conducting public talks to help people see that even in the finality of death, choices can be made and others can benefit from them.

Medical students observing a moment of silence in the respect ceremony.

Paying respect to the ‘great body teacher’

Bodies are important to the learning of future doctors, but until recently they were in short supply in Hong Kong’s medical schools.

Only a few years ago, anatomy students of the Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine had fewer than five bodies per year to work on. Now they are meeting their target of 20, thanks to the efforts of Dr Chan Lap-ki, the Assistant Dean of Pedagogy, who has been promoting body donation. His goal is to serve the needs of his students and, by extension, the general population.

“There is a very big difference between models and software that are designed for anatomy classes, and the actual body. Those tools idealise the human body and its structures, but in the actual body, things are not so well-defined. And everything is red, there are only slight differences in colour. This is something students need to learn,” he said.

Students are also expected to honour what is known in Chinese as the ‘great body teacher’. A respect service is held in the anatomy dissection class each year, and students must write a reflective essay on their feelings at seeing a dead body for the first time. “Many of them say it makes them realise how serious their chosen study is,” Dr Chan said.

The show of respect extends beyond the classroom. A memorial wall has been set up at Junk Bay Chinese Permanent Cemetery where families can scatter the ashes after the great body teachers have done their educational duty.