At what stage can patients with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia be said to be doing well? Is it when their disease is in clinical remission? Or is there something more? These are ongoing concerns in the field of mental health and they have been put to the test in a joint study by Dr Samson Tse in Social Work and Social Administration, Dr Chung Ka-fai in Psychiatry and faculty of Yale University.

They looked at 75 people in Hong Kong with bipolar disorder and 75 with schizophrenia who were all in clinical remission to determine the factors behind their ‘personal recovery’ – that is, their ability to find meaning in life and to live beyond their disability.

“Our focus is on positive transformation and a good sense of wellness beyond symptoms,” Dr Tse said. “My feeling is that especially among Chinese, we have a tendency to think that, if I’m still taking medication, I am sick and unwell. That what will make me well is if I no longer take the medication.

“This is a misconception and it is important. Because even if I’m taking medication and carry a label of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, I can still live well and find meaning in life. I can still function in work and interpersonally. Maybe not work full-time, but it is the journey of getting better.”

We have a tendency to think that, if I’m still taking medication, I am sick and unwell. That what will make me well is if I no longer take the medication. This is a misconception.

Dr Samson TseDifferent needs for different illnesses

That journey varies according to the disease. Personal recovery in patients with bipolar disorder is determined by what Dr Tse called ‘HER’ – hope, empowerment and respect. Because patients suffer a high recurrence rate, they need to feel they can come back to a recovery point again or even anticipate and mitigate recurrence.

“During an episode, patients can be doing very well. They can hold down a job and do well interpersonally. But the up and down rollercoaster of the disease can be very destroying,” he said. “They also need people to look beyond their disease and recognise what they do well in terms of their occupation or relationships.”

Schizophrenics, who suffer from hallucinations and delusions, benefit most when they have a meaningful life role to which they can anchor themselves. “Their major problem is that their world looks real but it isn’t, and this disturbs them tremendously. When they recover, the most deciding factor is finding a meaningful life role so they can relate themselves to their surroundings in a concrete, specific way.”

Overall, bipolar sufferers tend to do better in terms of employment, relationships and other aspects of everyday living, probably because they have wellness episodes. Schizophrenics have traditionally been closeted away in sheltered environments, but Dr Tse said his team’s research indicated that they needed quite the opposite approach – they needed a purpose in the community.

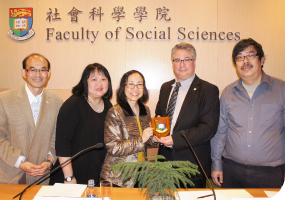

A research cluster was set up with the Program for Recovery and Community Health, School of Medicine, Yale University, to develop and disseminate findings and enrich understanding of mental illness. A Memorandum of Understanding signing ceremony cum seminar was held on March 17.

A research cluster was set up with the Program for Recovery and Community Health, School of Medicine, Yale University, to develop and disseminate findings and enrich understanding of mental illness. A Memorandum of Understanding signing ceremony cum seminar was held on March 17.

Dr Samson Tse (first from left), Professor Cecilia Chan (centre), Professor Larry Davidson, Professor of Psychiatry, Yale University (second from right) and two service users.

Dr Samson Tse (first from left), Professor Cecilia Chan (centre), Professor Larry Davidson, Professor of Psychiatry, Yale University (second from right) and two service users.

User input aids understanding

An important aspect of the project is that it was designed with input from ‘service users’, patients who were high-functioning and not subjects in the study. The users gave feedback on the questionnaire administered to subjects (such as advising that it be kept short so as not to overtax patients) and on interpreting the results.

For example, they helped to explain the unexpected result that lifetime binge drinking was associated with better personal recovery among bipolar patients. The users suggested drinking may be used to mask the mood fluctuations of the disease, or was related to the social side of the disease, as bipolars can be very sociable. Drinking might also be a way of preserving social connections as the disease develops.

Involving users as partners in this context of research is a cutting-edge practice that Dr Tse has brought to HKU. This spring he also set up a small research cluster jointly with the Program for Recovery and Community Health at Yale School of Medicine involving both service users and academic researchers, to develop and disseminate findings and ultimately enrich understanding of mental illness.

“We need to enter their world. The user’s world view is critical,” he said. “Patients also need to feel understood instead of having people pathologise their experience. Even their families often label them so if they’re moody they’re told, ‘you’re having an episode again, you need to get treatment.’ Our aim is not to label people but to say that recovery is a journey. We can be at different stages of the journey and no two people have the same journey. Our work is to help people understand that.”■