THE PEOPLE’S PERSPECTIVE

How Hong Kong residents identify themselves – as Hongkonger, Chinese and/or other – is changing and will have implications for the development of civil society. Dr Robert Chung Ting-yiu, Director of the Public Opinion Programme, and Professor Eliza Lee Wing-yee, Director of the Centre for Civil Society and Governance, have been tracking the changes.

In 2008, as China was gearing up to host the Olympic Games while at the same time recovering from the devastation of the Sichuan earthquake, an unusual yet understandable thing happened: Hong Kong people reported that they felt more Chinese than ever.

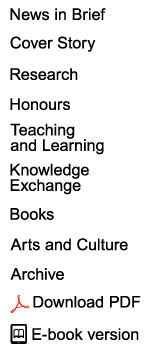

The finding was reported by HKU’s Public Opinion Programme (POP), which in 1997 began tracking whether people identified themselves as broadly Hongkonger or broadly Chinese, as well as the strength of that affiliation. In June, 2008, people rated the strength of their Chinese identity stronger than their feelings as Hongkongers (8.0 versus 7.8 out of 10). This had happened only a couple of times before, around 2002–2004 when dissatisfaction with the Hong Kong Government was strong and China was emerging as an economic powerhouse. It has never happened since.

Dr Robert Chung Ting-yiu heads the POP, which conducts its surveys every few months. He notes that while people’s identity affiliation has fluctuated over the years – through such events as the handover, SARS, the July 1, 2003 protest march, China’s economic boom as well as the Olympics success – it has taken a much sharper, more fractured turn in recent times. In fact by the end of last year, people’s sense of Chineseness was at 6.6, against 8.1 for the Hongkonger identity. For young people aged under 30 the results were even lower at 4.9 for their Chinese identity and 7.9 for their Hong Kong identity.

“The strength of people’s Hong Kong and Chinese identities was pretty similar from about 2000 to 2010,” he said, “then the strength of the Chinese identity began to drop. The drop was particularly big among young people. It was a kind of warning.”

Intertwined with that shift has been the rise of civic activism. Although Occupy Central is the most high-profile instance, there have been several other pivotal examples, such as protests against the Hong Kong-Guangdong high-speed rail link and the demolition of the Queen’s and Star Ferry Piers. These developments, says Professor Eliza Lee Wing-yee, Director of the Centre for Civil Society and Governance, are rooted in people’s affiliation with their Hong Kong identity, as well as their changing values.

“People are increasingly relating the heritage and use of space with a sense of themselves as citizens of this city. For example, a decade ago there was a big social movement against unlimited reclamation of Victoria Harbour. Why was it so important? Because the Harbour symbolises Hong Kong. People would proudly say it’s one of the most beautiful harbours in the world. And they had a lot of memories and personal experiences related to it, maybe as lovers or with their families. They did not want it to disappear because they felt that then a big part of their identity and collective memory would disappear.

“We saw the same thing with the later campaigns to protect Queen’s Pier and the Star Ferry Pier. A lot of the civic activism we have seen in the past 10 years has to do with citizens’ stronger awareness and consciousness of their identity and their connection to this place. They want a sense of ownership over policy-making,” she said.

![]() A lot of the civic activism we have seen in the past 10 years has to do with citizens’ stronger awareness and consciousness of their identity and their connection to this place. They want a sense of ownership over policy-making.

A lot of the civic activism we have seen in the past 10 years has to do with citizens’ stronger awareness and consciousness of their identity and their connection to this place. They want a sense of ownership over policy-making. ![]()

Professor Eliza Lee

Home ownership

The roots of that shift stem from the 1970s, when the first generation to be born mostly in Hong Kong came of age. They felt Hong Kong was their home – unlike their parents who were largely refugees and thought of home as their village in China – but they were also focussed on improving their material lives in terms of acquiring better quality flats and possessions and education for their children. They were seemingly unconcerned about things like heritage conservation.

“If you look at the 1980s a lot of buildings of historic value were bulldozed by the Government, one by one, without any public discussion,” Professor Lee said. “The argument was that this was important for economic development. In the 1980s and 1990s people passively accepted that argument or maybe agreed with it. They associated skyscrapers with modernisation and development and wealth.”

But as historic buildings kept disappearing– buildings that, like the Harbour, were part of people’s memories and experiences of the city– and the city became saturated with shopping malls and skyscrapers, more and more questions started being asked. Who was benefiting and were they doing so at the expense of others? Was this the right development model for Hong Kong? The handover in 1997 and subsequent events sharpened the discussion.

“1997 was a watershed because it symbolised the end of colonialism, the beginning of one country-two systems and the idea of ‘Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong’. It gave a new political identity to Hong Kong people – they were not colonial subjects but masters of this city state.

“2003 was another watershed. On the one hand there was the mass rally [on July 1] when more than half a million people took to the streets. On the other hand there was SARS. It’s been argued that both incidents strengthened Hong Kong people’s sense of citizenship because they felt empowered” – the rally for obvious reasons but SARS because people felt they could not rely on the Government to protect their health so they had to take matters into their own hands.

That sense of empowerment was a spark to social activism, which has mushroomed overthe past decade, she said. Some actions have been successful – the legal battle to constrain reclamation in Victoria Harbour and the protest against national education in 2012, for example– while others have failed, such as the Star Ferry and Queen’s Piers and Occupy Central.

“The rise in citizens’ demand to be actively involved in policy-making and the rise in local Hong Kong identity are closely connected and self-reinforcing. The more activist people become, the more it fosters a sense of citizenship, which also relates to their sense of place identity,” Professor Lee said.

HKU’s Public Opinion Programme has been conducting surveys on people’s categorical ethnic identity since 1997.

Number crunching

Dr Chung’s data reveals some interesting shifts in identity alongside these developments. At first, events tended to impact more on people’s Hong Kong identity than their Chinese one. In 2003 when dissatisfaction with the Hong Kong Government soared, the strength of people’s Hongkonger identity dipped from 8.0 in March that year to 7.4 in December. Chinese identity saw a smaller decline, from 7.8 to 7.5. “People were upset with the local Government and in terms of identity, people’s self-esteem went down as Hongkongers. But they did not blame the National Government,” he said.

That generally positive outlook persisted until about 2009, when the numbers for Chinese identity began to drop, especially among the young. This outcome attracted criticism of Dr Chung and his polling, but he pointed out their intention was only ever to provide academically-rigorous data that could be used by others to analyse Hong Kong’s post-1997 development, and see how the concept of one country-two systems was playing out culturally.

Respondents are not given a definition of ’Hongkonger’ or ’Chinese’ but simply asked to provide a figure up to 10 of their perceived strength of affiliation. They are also asked separately to state their ethnic identity; in December, 2015, 68 per cent said Hongkonger or Hongkonger in China, while 31 per cent said Chinese or Chinese in Hong Kong. (Other identities have also been added in recent years including ’member of the Chinese race’, ’Asian’, ’global citizen’ and ’citizen of the People’s Republic of China’. But Hongkonger and simply Chinese attract much more attention.)

Among 18–29 year olds, the strength of Chinese identity has fallen most sharply, from 7.4 in December, 2007 (the last time it was this high) to 4.9 in December, 2015, while the strength of Hong Kong identity in the same period has held steady (8.0 in 2007 and 7.9 in 2015). The effects among the over-30s are less pronounced but still, for the population as a whole, the Chinese identity remains well below 7.0 (the lowest point was 6.5 in December, 2014; in December, 2015, it was not much better at 6.6).

“A rating of 10 is absolute identification, zero is no identification and five is a half-half feeling. Anything below five would be a negative affiliation,” Dr Chung said. “The hard facts are that people’s feelings or identity in terms of being Chinese have dropped, and among young people it is turning negative.”

![]() The hard facts are that people’s feelings or identity in terms of being Chinese have dropped, and among young people it is turning negative.

The hard facts are that people’s feelings or identity in terms of being Chinese have dropped, and among young people it is turning negative. ![]()

Dr Robert Chung

Value change

Those feelings are channelling into civil society, where young people have been taking a leading role. Tens of thousands of people joined the 2012 protest against the proposed teaching of national education in Hong Kong schools, led by then-15-year-old Joshua Wong Chi-fung. University students played an active role in the Queen’s Pier and Star Ferry Pier protests. And of course Occupy Central was led by young people.

It might seem obvious that youths would take part in such actions – that acting on one’s ideals and being frustrated with the establishment are all part of being young. But Professor Lee said the situation was more complicated than that.

“Some of the older generation and pro-establishment people attribute youth activism to the decline in social mobility because young people are finding that it is not so easy to rise up the ladder. There is an element of truth to that, but I do not think it is the only cause for the rise in activism.

“In the US in the 1960s and Europe in the 1970s, many protest movements were driven by post-material values, such as equality, social justice, peace, environmentalism, gender and racial equality. They were not protesting about things related to material gain. When people become focussed on those values, it can be seen as a sign that a society has developed to a certain stage of affluence.

“I have spoken with university students in Hong Kong who do not feel that making a lot of money is their purpose in life. They want to make the world a better place, whether it is fighting for the environment, against poverty, for global justice or whatever their cause. The younger generation is much more prone to this kind of idealism.”

Young people also are finding other outlets besides street protests to express their views, she said. For example, the website TVMost has become hugely popular for satirising celebrities, the terrestrial broadcasters, and politicians and other establishment stalwarts. “Young people are taking their activism to new levels that are not necessarily about marching in the streets. They are finding more ways to assert their strong sense of local identity,” Professor Lee said – implying that this identity is still evolving. It may go up as well as down as Hong Kong continues to come to terms with its place in China and in the world.