The highly-publicised spate of suicides at Foxconn factories in Shenzhen in 2010 were a catalysing force for Professor Pun Ngai in the Department of Sociology, who had already earned accolades for her study of female migrant workers in China. Fourteen suicides were reported that year and Foxconn claimed they were due to personal reasons. But as the numbers escalated, the explanation failed to convince Professor Pun, who appealed to nine fellow scholars for immediate help to investigate working conditions at the factory – there was no time to wait for funding. That appeal started a snowball reaction that is still rolling.

More than 100 volunteer academics and students came forward, including 14 students who landed jobs inside Foxconn. The research revealed stressful working conditions, such as shifts that operated around the clock and a setup that discouraged workers from forming bonds lest they start to organise themselves (for instance, workers from the same village or community were purposely separated).

More importantly, the work enabled Professor Pun to identify a new group of working class in China that she estimated numbered as many as 20 million people: vocational school students.

These schools were encouraging students to work in all kinds of factories, not only during summer or winter breaks but as part of their final-year work placements, even though the work was often unrelated to their majors such as nursing, accounting, management and the like.

“We observed big buses picking up students at those schools and taking them to the Foxconn factory,” she said. “The students had hoped to learn a skill and climb the social ladder, but in reality they were being sent to work in a factory, doing very repetitive tasks. It made them feel they were wasting three years at the school.”

![]() The students had hoped to learn a

The students had hoped to learn a

skill and climb the social ladder, but in

reality they were being sent to work in

a factory. ![]()

Professor Pun Ngai

A gap between dreams and reality

Professor Pun’s research also takes a broader perspective on the situation at Foxconn, placing it within the greater context of the evolution of the modern working class in China. The first generation emerged in the 1980s and 1990s when China was opening up, and worked 14 to 16 hours a day, seven days a week. The second generation had it a little better with work scaled back to six days a week.

The third generation – the current one – has come of age when the central government is trying to upgrade the skills of its workers. “Their working life is getting better – their working hours are shorter and their salaries are higher than previous generations. But there is a gap between their dreams and reality and they have accumulated more grievances and desires simply because of the consumption culture. They compare themselves with urban workers and the middle-class lifestyle. I would say in the long run that is driving them to organise to improve their working conditions,” she said.

For example, the Foxconn workers she observed were aware of their labour rights and willing to join forces. “There will be more strikes, more proactive action, so the government has to try to find a balance between the two sides,” she said.

In addition to her research, Professor Pun is also raising awareness among workers in China by working with three vocational schools to develop a general education curriculum and website about labour protection and migrant issues.

Next

Back

TAKING ON FOXCONN

Professor Pun Ngai has produced critical research on the problematic working conditions in Foxconn factories and the state of China’s working class.

Campaigns for change

Her research showed schools had signed agreements with Foxconn to provide student workers, although this was much reduced after the spate of suicides. However, Foxconn subsequently expanded into the western part of China and found fresh recruits there – she even found instructions from one local government asking a vocational school to place their students at Foxconn.

“Usually the provincial leader is very happy to work with Foxconn because it will increase GDP, at least on paper,” she said. “The local and state governments and the company and school are working together to produce what I call a young migrant working class.”

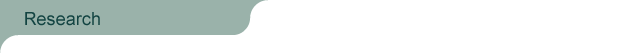

Professor Pun’s findings were shared in the media and with NGOs and became the basis of campaigns to improve working conditions. One group she worked closely with, Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour (SACOM), launched a high-profile campaign in 2017 to coincide with the 10th anniversary of the iPhone (Foxconn’s major client is Apple). This resulted in the firms’ pledging to improve students’ wages, stop students from working night shifts and allow for union elections. Apple even said it would stop employing student interns. But more recently, Professor Pun has received reports that the old practices are creeping back in.

While stopping students from working at Foxconn could affect their income, Professor Pun said it was important that students be offered appropriate internships in their disciplines, which are either lacking or require students to pay extra. “The students really need to learn and upgrade their skills so if this puts pressure on the vocational schools to find other vendors for these students, it is not necessarily a bad thing. But it will take time to improve the situation,” she said.

Since 2010, the Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour (SACOM) has run a series of campaign demanding that Apple and Foxconn stop their practice of forcing vocational school students to work excessively long hours in the iPhone production lines.

The Students and Scholars Against Corporate Misbehaviour (SACOM) launched the ‘iSlave at 10’ campaign in 2017 to coincide with the 10th anniversary of the iPhone.

Home

November 2018

Volume 20

No. 1