Next

“Burn it!“

“She even suggested at one stage that they simply burn the manuscript,” added Mr Merz. “Because of this, some people have questioned whether it should have been published after her death at all, but I think it should. Burning was only one of many emotions she expressed– at other times she had high hopes for its success in an English translation.”

Finally published in Hong Kong in 2009, Little Reunions became an instant bestseller and then in China and Taiwan, and now the English translation is being well received around the world.

Famously, Chang was an undergraduate at HKU, and the first part of the book covers this period in Hong Kong, including the first bombing of the city taking place just as she is about to start her finals. She talks about places familiar to local readers, including the original Repulse Bay Hotel and the Catholic Cemetery in Happy Valley and of taking walks in the hills surrounding HKU and looking out at all the little islands in the South China Sea.

Honest version

The story parallels her own life closely, in all its disarray. “It’s not an uplifting novel, but it is a great story,” said Mr Merz. “She is looking back at her seriously dysfunctional family and it’s often harrowing. Readers will recognise the story from her other works – she is using the medium of the novel to tell and retell her own story. But I think this is the most honest version and the one that most closely resembles her actual life.”

Little Reunions is the third book that Mr Merz has translated. His first major book translation was English: A Novel, a coming-of-age story by Wang Gang about a boy living in Xinjiang during the Cultural Revolution. Mr Merz studied Mandarin at Melbourne University in the 1970s, before working in Taiwan and Mainland China for 30 years. He also did a Master of Arts in Applied Translation at the Open University of Hong Kong with Professor John Minford, an expert in literary translation.

The book launch for the newly translated novel was hailed as ‘Eileen Chang’s triumphant return to HKU’ – a slight exaggeration perhaps, but since half the book is about her time as a student at the University it was not an inappropriate claim.

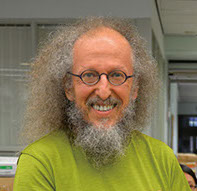

One of the translators, Australian Mr Martin Merz talked about the responsibility of bringing the final work of one of HKU’s most acclaimed students to English-speaking audiences. Translating Little Reunions took about a year, but before that process could even begin Mr Merz spent an initial 12 months doing preliminary research.

“Because the book is autobiographical, and because she was writing in the 1970s about things that happened from the 1930s and 1940s I needed to become immersed in the background of events she described,” he said. “By the time she wrote the book Chang was in her mid-50s, working in Los Angeles and was cut off from China, so relying on her memories only.”

He also had to work out who is who in the book. “We created a bilingual character list for our own reference as we progressed and in the end we included it at the end of the novel. There are over one hundred characters. In addition to calling herself Julie in the book – Chang is also writing about people familiar to readers of her earlier works Lust, Caution, The Fall of the Pagoda and The Book of Change.”

There is her mother, called Rachel here, long divorced from Julie’s father who – like Chang’s real father – is an opium addict, as well a complicated cast of relatives who crowd her life. Forced to return to Shanghai by the Japanese invasion of Hong Kong Julie falls passionately in love with the magnetic Chih-yung, a traitor who collaborates with the Japanese puppet regime. Like Julie’s relationship with her mother, her marriage to Chih-yung is marked by long periods apart interrupted occasionally by unexpected little reunions.

The author’s real-life husband Hu Lancheng was a Japanese collaborator during the Sino-Japanese war, who served briefly in the propaganda ministry of the puppet government in China headed by Wang Jingwei. “He was an awful man and was regarded as a traitor,” said Mr Merz. “But she loved him and after the war helped him escape to Japan.”

Such politically sensitive aspects of the book are the reasons it was not published when it was written in the 1970s. “Chiang Kai-shek had just died,” explained Mr Merz, “and her by then former husband, Hu Lancheng, was a politically sensitive figure. At the time she had long discussions with her agents [the parents of her current literary executor Roland Soong] about whether to rewrite the novel extensively to remove all sensitive material.

![]() It’s not an uplifting novel, but it is a

It’s not an uplifting novel, but it is a

great story. Chang is looking back at her seriously dysfunctional family and it’s

often harrowing. ![]()

Mr Martin Merz

Final chapter for

Eileen Chang

Eileen Chang’s final novel, Little Reunions, has been translated into English two decades after her death. The work covers her experiences at HKU before and after Japan invaded the city.

Martin Merz (second from right) at the book talk titled ‘Little Reunions: Eileen Chang’s triumphant return to HKU’ where Ilaria Maria Sala (first from right) was the moderator.

The two translators of Little Reunions – Jane Weizhen Pan (right) and Martin Merz (left).

Little Reunions

Author: Eileen Chang

(Translated by Jane Weizhen Pan and

Martin Merz)

Publisher: New York Review Books

When Mr Merz received the request to translate Little Reunions, he viewed it as ”an exciting opportunity given her prominence in modern Chinese literature.” He worked on the book together with Jane Weizhen Pan whom he describes as his partner in crime in translation. She grew up in China, and is currently doing a PhD in translation research.

“It’s good to translate as a team – it can be lonely work,” he said, “and it is entirely possible for a non-native speaker such as myself to get one word wrong and go off on a disastrous tangent. Jane ensures this does not happen.”

Summing up the experience, Mr Merz said: “This autobiographical novel proved to be both challenging and rewarding, providing a vivid entrée into a world that has long departed while offering insights into the human condition.”

Home

November 2018

Volume 20

No. 1