To understand the scale of Hong Kong’s construction waste problem, consider the state of the landfills. Hong Kong has three enormous landfills that were supposed to last until 2030 but are expected to fall a decade short of that in large part because of construction waste. About 28 per cent of landfilled waste in 2015 came from construction sites, which dumped on average about 4,200 tonnes per day.

“Hong Kong landfill space is extremely valuable, but this one single industry is taking up about one-quarter of the capacity. This is really a burning issue,” said Dr Wilson Lu of the Department of Real Estate and Construction.

What’s worse, the landfilled waste represents only five per cent of the building waste mountain. Inert waste, including concrete, boulders, bricks and sand, is too expensive to be taken to landfills and has to go elsewhere – either to public fill sites to await use in reclamation, or be shipped to China. Both outlets are becoming more restricted.

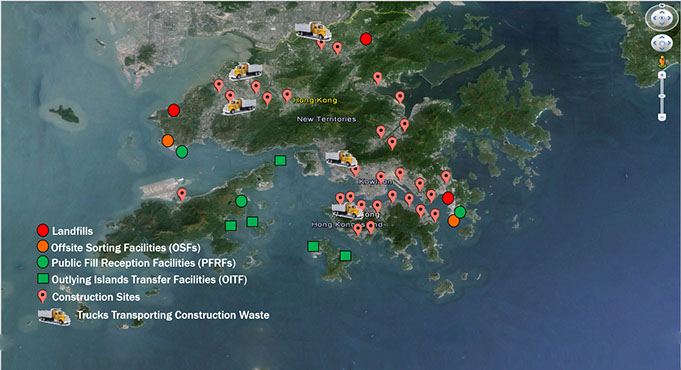

Dr Lu is trying to help address these challenges by using big data to understand the production and disposal of construction waste in Hong Kong. He is drawing on records related to waste charges, as operators are charged HK$71 to HK$200 per tonne of waste, depending on whether it goes to public fill sites, waste sorting centres or landfills.

![]() Hong Kong landfill space is extremely valuable, but this one single industry is taking up about one-quarter of the capacity. This is really a burning issue.

Hong Kong landfill space is extremely valuable, but this one single industry is taking up about one-quarter of the capacity. This is really a burning issue. ![]()

Dr Wilson Lu

Shining a light

In one line of research, he acquired data for 25,000 construction sites and found that, despite the waste charge, public projects produced less waste than profit-motivated private ones. “The reason is the cost of labour. An ordinary construction worker is paid more than HK$1,000 per day, so asking these expensive workers to sort waste is not economical. It’s cheaper for them to pay waste charges,” he said.

Some operators try to reduce both labour costs and waste charges by dumping their loads illegally, which can be difficult to catch in the act. This is another area where big data can shine a light. Dr Lu is trying to detect patterns related to illegal dumping by tracking individual operators, project type, location or a combination of these.

“We’re referring to research like that done in Cambridge University where they use big data to identify corruption. The approach is that you establish the criteria that indicate potential illegal dumping and screen all the data against those criteria. We’re now trying to train the model using the plate numbers of lorries that have been involved in illegal dumping in the past,” he said.

He is also using big data to help the industry benchmark waste generation rates by plotting the waste arisings from nearly 3,000 projects. These have been sorted into ‘good’, ‘average’ or ‘not good’ in terms of the quantities of waste they send to landfills over one year.

Yet another project has been looking at the waste from 808 buildings which have the Building Environmental Assessment Mehod (BEAM) certification. Dr Lu found that most of the points earned for the certification came from green measures in the construction and operation of the building, rather than managing construction waste.

‘Unethical’

Apart from crunching numbers, Dr Lu and his colleagues are also developing technology. For example, a platform is in development to address the bizarre situation in which local developers have to import fill materials from China even while the Hong Kong Government is paying to transport excess fill materials across the border. The reason is that the materials are often not available when the developers need them. Dr Lu’s platform would help match demand and supply more readily.

“It is unethical that 95 per cent of inert waste is hidden somewhere or simply sent to China. We don’t even recycle it – only a very small portion of this waste gets recycled,” he said.

Despite the problems, he believes Hong Kong has made good progress on construction waste management because the waste is tracked, there are charges for disposal, and the Environmental Protection Department maintains ongoing engagement with the construction trade.

This is all serving as an example to China. Dr Lu estimates waste loads there to be an unfathomable 1.13 billion tonnes per year but there are few proper systems in place for managing it. The problem came under the glare of the international media in 2015 when a huge pile of construction waste in Shenzhen collapsed, killing more than 70 people. “Shenzhen has now started to charge for waste disposal and to use tracking technologies. They are learning from Hong Kong,” he said.

The Trouble With Rubble

Construction waste in Hong Kong is a major problem. As the city continuously builds and rebuilds itself, it is running out of space for its building waste. Dr Wilson Lu has been using big data to investigate.

A display of big data analytics for construction waste management.

The benchmarking system for projects to compare their construction waste management performance against industrial standards.

Next

Back

The big data generated from construction sites in Hong Kong.