Minorities in any country tend to be marginalised, and so do their languages. When people emigrate to a new country a part of their culture that may be left behind is usually their language. While this may be considered part of a natural evolution – adapting to survive in a new environment – it does mean languages can be lost.

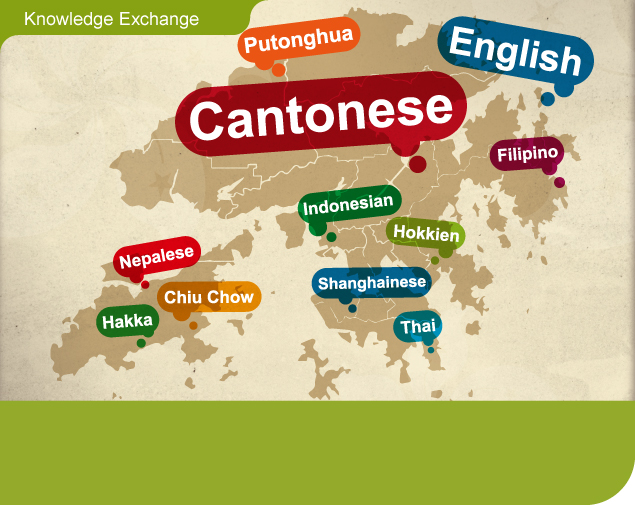

Ask what language is spoken in Hong Kong and the snap answer is Cantonese, with English and Mandarin thrown liberally into the mix. But Hong Kong’s population is far more multicultural, and the variety of languages spoken much wider. A new linguistic website, LinguisticMinorities.HK aims to give those minorities a voice – a voice that speaks their own language.

Dr Lisa Lim who set up the website says it was not until she came to live in Hong Kong that she realised the extent of the varieties spoken here. “I’m from Singapore, and arrived here with a pretty stereotypical image of Hong Kong. It was only when I lived here that the diversity within Hong Kong really emerged.”

The website, which has just won the Faculty Knowledge Exchange (KE) Award for 2014, came about as a result of a Language and Communication programme capstone course she has been teaching since 2009 on minority and endangered languages – one of her research interests – which involves both theoretical ideas and hands-on fieldwork. Students work within minority communities in Hong Kong to investigate the linguistic issues facing them, such as language shift across generations, or language challenges in education. They discovered that information is scattered across government websites and non-governmental organisation websites, little first-hand research had been done, and nothing had been consolidated.

Dr Lim also came to realise that most of her local students didn’t engage with minorities. “The course started them doing that, and their projects were wonderful. They produced websites or blogs, and it was detailed, interesting, wonderful work. It made me think: why am I the only person seeing this

work – other people would also find it useful.”

I want [the website] to be an academic resource for academics, journalists and policy-makers, and to contribute to decision-making on diversity and inclusion.

Dr Lisa LimUrban multiculturalism

Another reason for the website was that there has been growing interest, political and academic, in other parts of the world, particularly Europe, in the multiplicity of cultures within cities. Known as urban multiculturalism, or urban diversity, it has come about because of changes in immigration policies which have opened up borders in Europe. Less attention, however, has been given to the diversity in modern cosmopolitan cities in Asia, such as Hong Kong.

Dr Lim hopes the website will put Hong Kong’s linguistic diversity on the map, and increase awareness among the public, be they local Hongkongers, or members of minority communities in Hong Kong, or across the region.

She would especially like it to be a platform for minorities, “so they can feel represented and thereby validated. It may also raise the possibility of their having a voice. I also want it to be an academic resource for academics, journalists and policy-makers, and to contribute to decision-making on diversity and inclusion.”

An unforeseen result of the website has been interest from the younger, internet generation in Hong Kong. “Some of my students were surprised to see Chinese minorities, such as Hakka, Hokkien and Chiu Chow, included. They thought minority meant something more exotic. Some said, my ancestors are these ethnicities, but it was the first time they had engaged their grandparents in conversations about their roots.”

Finally, it’s a showcase of research and expertise within the Faculty and University, both by staff and students. “The website is constantly growing and is a collective effort. It’s good for students to see their work up there – I think it encourages them. And they really enjoy the experiential learning – they say the best part is going out and meeting people from minority communities.”

Backed by a third round of KE funding this year, the next step is to translate the website into Chinese, making it even more accessible to the local community. Feedback from colleagues, journalists and laypeople has been good, and the website has had tens of thousands of hits from around the world – about 50 countries in all.

Content includes videos of interviews with members of minority communities, and these throw up some interesting discussion points pertinent to attitudes in Hong Kong. For example, a 50-year-old Hakka woman commented: “I don’t like (to speak) Hakka anymore – I might be mistaken for a Mainlander.”

Concluded Dr Lim: “It couldn’t have happened without the hard work of my students, and their excellent and inspiring work on the course, and of course, the receptiveness and support of the communities themselves. It’s especially gratifying when one’s research, teaching and knowledge exchange come together in such a dynamic way.”■