The China-Myanmar border may not be a financial hub, but it buzzes with illicit economic activity. Truckloads of timber cross from Myanmar to Ruili in Yunnan province, China, and from there to factories on the eastern seaboard, bearing customs papers that wrongly claim the wood is from China. Money is often transmitted well out of sight of the formal banking system, and people take advantage of large gaps between customs checkpoints to transport goods and themselves back and forth across the border.

To Dr Victor Teo of the School of Modern Languages and Cultures, the area is a vibrant example of a border economy where the boundaries exist largely in name only. These areas tended to be neglected by scholars, he said, not least because of the difficulty in obtaining data and information.

Dr Teo has stepped into this lacuna with research on the activities and traders along China’s borders with Myanmar, North Korea, Russia, Central Asia and India.

“The idea of a border is an abstract and constructed one. We tend to think of border areas as neglected and economically backwards, but actually they are areas of intense interactions among people. The interactions may be off the books and not recorded, but they are immense, and the borders hold different meanings for different categories of people in China,” he said.

We tend to think of border areas as neglected and economically backwards, but actually they are areas of intense interactions among people. The interactions may be off the books and not recorded, but they are immense.

Dr Victor TeoEarning money, moving money

Tibetan selling fake tiger skin in Guangdong province.

Tibetan selling fake tiger skin in Guangdong province.

Dr Teo’s informers are traders, residents, drivers, smugglers and other contacts he has cultivated for years in an effort to understand the workings of the economy on the borderlands from the perspectives of both international relations and anthropology.

In North Korea, despite official assertions that markets do not exist in the country, he has found institutionalised spaces where trading takes place. Many products are brought in officially or smuggled in and resold by traders for a profit. Very often, border guards get a piece of the action.

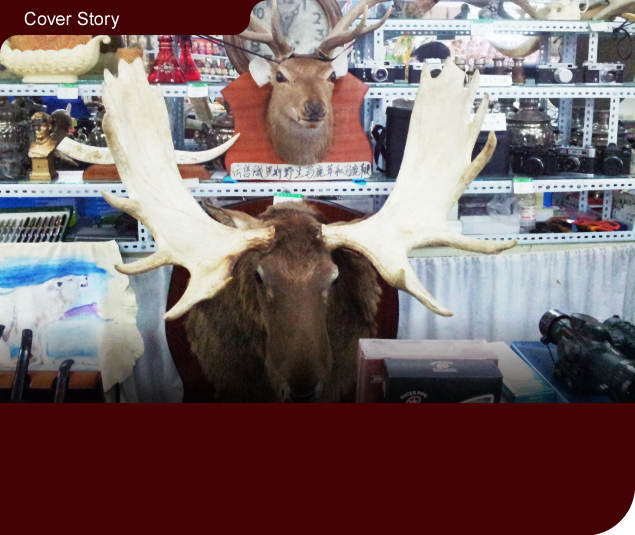

Russia’s border with China is even more fluid. Bear paws, wolf pelts and other animal parts are smuggled out and Dr Teo said in some places customs officials ferry goods across for traders for the right price.

Most important to all these activities is underground banking, which offers lower charges, a faster service and none of the limits on overseas transactions that are found in the legitimate banking system. This phenomenon should not be underestimated, particularly along China’s southern borders where it services legitimate businessmen, corrupt officials, criminals and traders operating in the ‘grey’ market, he said.

The transactions are made by giving cash to a ‘banker’ in China, who will text or call their contact in Hong Kong or Macau to tell them the amount and currency that will be picked up. Money also flows the other way.

“With an electronic text or passcode, the money can be picked up or transferred easily. Thousands of these transactions take place each day and they are undocumented. Physically, the money doesn’t actually cross the border,” Dr Teo said.

Traders of parallel imported milk powder at the Shenzhen-Hong Kong border.

Traders of parallel imported milk powder at the Shenzhen-Hong Kong border.

Fuel for inflation

Two ladies crossing the China-Myanmar border via the small hole in fence (highlighted in red).

Two ladies crossing the China-Myanmar border via the small hole in fence (highlighted in red).

All of this points to sound economic reasons for studying and understanding the border areas and the underground economy.

“The Chinese Government has such a hard time reining in inflation especially in the southern cities. That has a lot to do with the underground economy. Regardless of the policies instituted, the funds that flow out of the borders often end up coming back into the country into legitimate business and the real estate sector. The Government doesn’t have control over these kinds of activities.

“The remittance system is not new. Generations ago, many Chinese who went overseas to Southeast Asia or the United States had to send money back to their families in China. They made use of the trading houses in China for transmitting money back home.”

In fact, he said: “Many people who partake in the underground economy are not criminals but simply traders who are exploiting differentials in the demand and supply of certain categories of goods.”

Dr Teo is bringing all of these observations together in a forthcoming monograph, tentatively titled Clandestine Globalisation and China’s Borderlands. He also organised a conference last year that looked at China’s underground economy in relation to the illicit industries around fake goods, which run the gamut from fake handbags and watches to fake medicines. The bottom line for all these activities is to turn a profit.

“People don’t think of it as an underground economy but a way to build better lives. For them the state and governance are abstract concepts,” he said.■

Dr Victor Teo (second from right) participated in a knowledge exchange workshop titled ‘Global Governance, Underground Economy and its Impact on Health and Human Security in Greater China and East Asia’ to share his views on the illicit pharmaceutical industry in China.

Dr Victor Teo (second from right) participated in a knowledge exchange workshop titled ‘Global Governance, Underground Economy and its Impact on Health and Human Security in Greater China and East Asia’ to share his views on the illicit pharmaceutical industry in China.