| East-West Mixtures

Improve Mental Health |

|

| Professor Zhang Zhangjin of the School of Chinese Medicine has been showing how and why acupuncture and herbal medicines help patients with mental health problems, through modern evidence-based research. |

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is concerned not only with physical health but also mental well-being. That well-being has been under threat in Hong Kong and Mainland China over the past three decades, where rapid modernisation has been accompanied by a large increase in such problems as depression and mood and psychotic disorders. Professor Zhang Zhangjin of the School of Chinese Medicine is showing that traditional Chinese medicine offers promise to alleviate these modern-day problems. Professor Zhang was trained in both TCM and Western medicine and conducted psychiatric research at American universities for more than 10 years before arriving at HKU in 2006. He believes the two traditions can be brought together to improve patient outcomes. “In general, especially in Western countries, the treatment for most psychiatric patients is limited to certain pharmaceutical medications, but these medications have shortcomings. For example, only 60–70 per cent of patients respond to anti-depression drugs, so there is still a large portion who cannot obtain a satisfactory clinical response. More than 75 per cent of schizophrenia patients relapse within one year if they stop taking their medication due to the side effects. So we need to look for alternative treatment strategies.” “I want to bring neuroscience, TCM and psychopharmacology together to help people get better clinical care for mental problems.” Reducing side effects At HKU, he has collaborated with researchers in Beijing to show that a traditional herbal preparation called Peony-Glycyrrhiza Decoction (PGD – shao yao gan cao wan) can alleviate the side effects of antipsychotic drugs in women with schizophrenia. The antipsychotic drugs increase the production of prolactin, which results in breast milk secretion, menopause, menstrual pain, reduced libido, hair growth and spots. The side effects lead many patients to give up the drug, resulting in a relapse of their condition. In a clinical trial of 20 patients, Professor Zhang and his collaborators showed PGD could reduce the symptoms. A larger trial involving 118 patients is now being conducted with support from the Hong Kong Department of Health. In the meantime, laboratory studies have shown the mechanism by which PGD works, adding to the weight of evidence of its efficacy. |

|

“I want to bring neuroscience, traditional Chinese medicine and psychopharmacology together to help people get better clinical care for mental problems.” |

Professor Zhang performs acupuncture treatment on a patient Professor Zhang performs acupuncture treatment on a patient |

||

| Professor Zhang Zhangjin |

|

Acupuncture is another treatment he is testing, focussing on patients with depression. Depression is usually treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) drugs that, in young patients, can take four to six weeks to take effect and can even worsen their condition. Professor Zhang showed that acupuncture could speed up the effects and help lead to a better outcome, through a trial on 72 patients in Hong Kong. The improvements were reported in both doctor and patient assessments. “Even after one session of treatment, the patients receiving acupuncture had a much better clinical response compared to the non-invasive control group, which means acupuncture can indeed speed up the therapeutic response of SSRIs,” he said. Not a placebo Acupuncture was further tested in a six-week randomised controlled trial involving 160 patients with major depressive disorder in Guangzhou. Patients received either the SSRI paroxetine, paroxetine plus manual acupuncture, or paroxetine plus electrical acupuncture. They were assessed during the trial and four weeks afterwards, and the latter group showed the best sustained improvements. “This finding is very important because it indicates that acupuncture is not a placebo effect,” Professor Zhang said. “The second conclusion is that electrical acupuncture has a long-lasting effect in reducing depression symptoms.” A follow-up clinical trial using neuroimaging, positron emission topographic (PET) scans and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) showed that the brain indeed responds to acupuncture treatment for depression. |

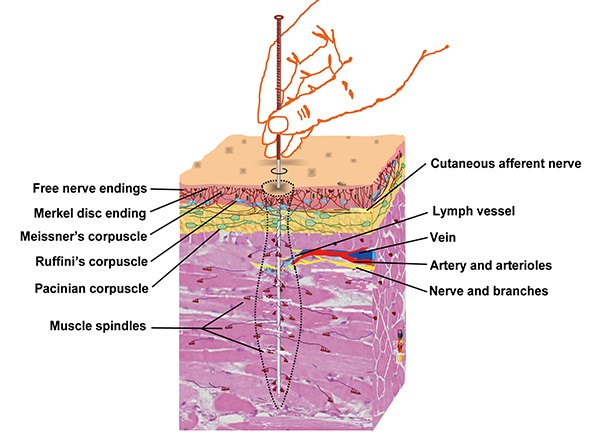

A representative muscle-spindle-rich neural acupuncture unit in response to manual twists of acupuncture stimulation |

|

Explaining how acupuncture works Those findings do raise a question, though. How is the acupuncture working? There are more than 300 recognised acupoints in traditional Chinese medicine and researchers have been trying for years to understand them. Professor Zhang and his team propose defining acupoints as a ‘neural acupuncture unit’ – places where the neural and neuroactive components that transmit acupuncture signals to the brain are relatively dense and concentrated. This is a term and concept more easily understood by modern scientists than traditional explanations, he said. “Acupoints are a metaphysical concept from ancient times – they are the places to which meridian energy flows and is infused into the tissues and organs. We need to advance such metaphysical concepts and update them in the framework of modern biomedical knowledge,” he said. That work, together with the clinical trials, is helping to provide evidence that can convince the international medical and scientific communities of the effectiveness of TCM remedies. |

| Back | Next |