| A Living History | |

| Heroes and traitors, fighters and founders – Dr Peter Cunich’s history gives HKU a fascinatingly human face. |

|

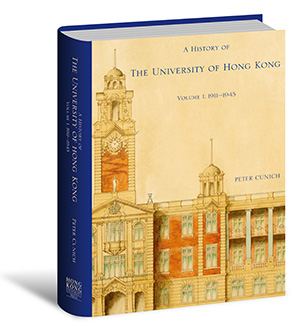

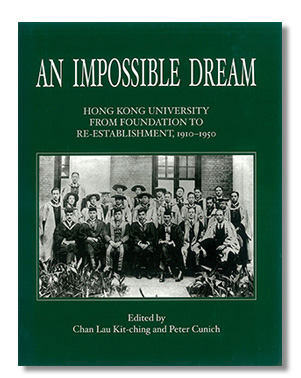

An Impossible Dream: Hong Kong University from Foundation to Re-establishment, 1910–1950 published in 2002 was a 90th-anniversary project by Faculty of Arts. |

As HKU celebrates its centenary it is only fitting that a scholarly work on the University’s history should be produced. What is perhaps more surprising is that the work that has emerged is not only the history of an institution but also a very lively, very human narrative. “This was deliberate,” says author Dr Peter Cunich. “We began thinking about the centenary book back in 1999 when we were compiling An Impossible Dream, the book to mark the University’s 90th anniversary. I was determined that the centenary book should have an authentic voice. I didn’t want to simply retell the administrative and constitutional history; I also wanted to have people’s personal experiences within the text.” To this end, he began interviewing as many of the pre-war and war-time students as he could track down. “From 2003 on, I started seeking out graduates and alumni who had been at the University before 1941, war-time students and those involved in re-establishing the University post-war. Hopefully readers will identify with these first-hand accounts.” |

Most of those interviews contributed to what would become Dr Cunich’s favourite chapter, Chapter 9 which covers the War years. “The stories I was told were fascinating. It emerged that in the 1940s, HKU was on the international stage in a way it had seldom been up until the last few years when we’ve become one of the top 25 universities in the world.” |

| “The War allowed these students to do all three things at once – they could fight for their home, show that they held to Western ideals, and at the same time be Chinese patriots by fighting for China.” |  An interior view of the roofless Great Hall in the Main Building, taken after the World War II. |

||

| Dr Peter Cunich |

|

Traitorous acts The University, both faculty and students, played an important role in World War II – much of it noble, but some of it less so. “The point that I make in Chapter 9 is that you have a range of reactions to the Japanese [invasion of Hong Kong]. Some people resisted, others went along with it in the quietest way they could, while others actively collaborated and committed traitorous acts,” says Dr Cunich. “While the older generation tended to try to look after themselves, the younger students and graduates went to free China, joined the British Army Aid Group (BAAG), the Chinese Army, various other units of the British Army, even the US Air Force, actively fighting against the Japanese.” “What is interesting – partly because it has relevance today – is that they were fighting for a mixture of things: their home – whether that was |

|

Hong Kong or Malaya – defending their home from the Japanese. But they were also fighting for Britain because most of them saw the Japanese as the aggressors and Britain as upholding the values of civilisation (significant because this is what the University was originally meant to inculcate – a love of Empire). And then the third level was Chinese patriotism.”

“The War allowed these students to do all three things at once – they could fight for their home, show that they held to Western ideals, and at the same time be Chinese patriots by fighting for China.” Dr Cunich feels that this fits in very interestingly with some of the current controversy about Hong Kong identity. “Today there is a polarisation, a feeling that you can only be one thing or the other. For these war-time students they could be all three at once and there was no paradox in that. They come out of the whole experience completely changed people and many went on to become leaders in Hong Kong, Singapore or Kuala Lumpur, taking up roles in society that pre-war graduates were not able to do.” Dispelling urban myths While writing Chapter 9 proved a fascinating experience, other areas of the book were more problematic. “Some of the urban myths that over the years have been established as history are difficult to dislodge,” says Dr Cunich. “For instance it is widely accepted that Dr Sun Yat-sen was a graduate, and many still believe that HKU started with only two faculties, Engineering and Medicine, and Arts came later.” |

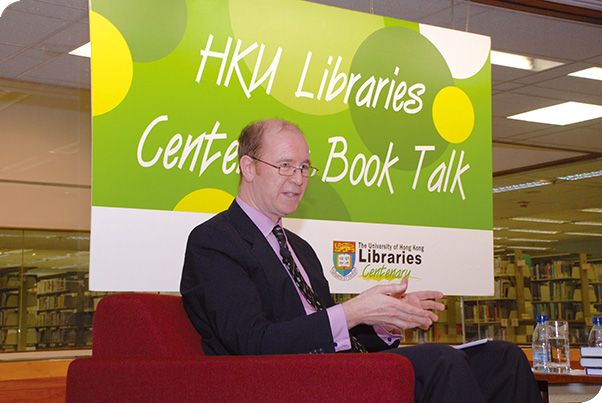

Dr Peter Cunich at the HKU Libraries Centenary Book Talk: Forging a HKU Identity, 1905–1945. |

| “The reason I dedicated the book to the students in the War years is because their stories are exceptional – in any time or place these are stories that are legendary.”

|

||

| Dr Peter Cunich |

||

|

The book corrects both. Dr Sun Yat-sen was a licentiate of the Hong Kong College of Medicine for Chinese, which was founded in 1887. And while it is true that HKU’s founder Sir Frederick Lugard did not want a Faculty of Arts because he feared it might inspire insurrection and radicalism within the student body, the local Chinese community insisted on establishing an Arts Faculty. Another problem was the mammoth task of gathering information on the University, much of which came from abroad – the Colonial Office and the School of Oriental and African Studies archives in London, plus other material in Russia, Germany, the US and even in Australia – and then condensing it all into a book. “There was so much we didn’t know, including information in our own archives,” says Dr Cunich. “As we approached the deadline, the sheer size of the text was a problem.” A decision had to be taken on whether to cut much of the text or go to two volumes – that second volume, covering the second half of the century, is currently being written. Instrument of Empire Having gone through so much material, Dr Cunich feels that one of the most important discoveries has been the light that has been shed on the very early years and the role that HKU played in imperial policy in China. “The idea that HKU was somehow going to be an instrument of Empire that would help the British establish good relations with China was central to the University’s role,” he says. “The intention was to do this through cultural imperialism and HKU became more and more the centre of that policy.” While founder Sir Frederick Lugard held this view back in 1911 when HKU was established, London only really agreed with it in the 1930s when China was at war with Japan and Britain was trying to help China, while at the same time competing with the Americans. “They saw HKU as one of the ways to get a foot in the door,” says Dr Cunich. |

|

The name of Lugard recurs frequently throughout the book. While this is unsurprising at the start, few have realised until now how long his influence continued. He left Hong Kong in 1912 but continued to support the University until his death in 1948. Dr Cunich interviewed Lugard’s great niece who said he considered the University his greatest achievement. That interview would also bring to light the original architectural drawings of the Main Building that were used on the cover of the book. “It was a great coup to get the original drawings back as we thought they had been lost.” Dr Cunich has been a historian with HKU for the past 20 years, but he says that writing this book threw up many new discoveries and became an inspirational experience. “Meeting such fascinating people and hearing their extraordinary stories has been very inspiring – far more so than I originally expected,” he says. “The reason I dedicated the book to the students in the War years is because their stories are exceptional – in any time or place these are stories that are legendary.” |

Sir Frederick Lugard, Chancellor 1911–1912. |

| Back |