|

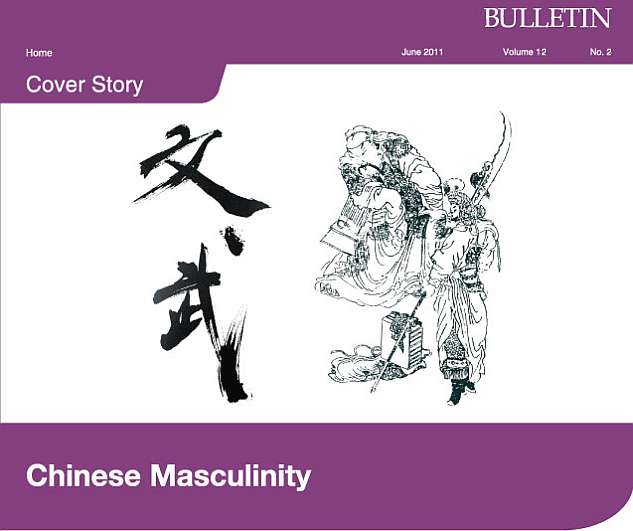

When Professor Kam Louie, M.B. Lee Professor in Humanities and Medicine and Dean of the Faculty of Arts, was studying in Australia some years ago, the 'he-man' concept was popular. Men like James Bond and Rambo were the ideal, while Chinese men were seen as geeks and nerds. As a Chinese man, it got him wondering, what attracts women? And what qualities define the ideal man? This led to a groundbreaking book, Theorising Chinese Masculinity: Society and Gender in China, that draws on literature, opera, film and other cultural vehicles from the past and present. Chinese masculinity is structured by two archetypes: the scholar (wen) and the warrior (wu). Confucius is the model wen, a refined intellectual of the gentry class, while the god of war Guan Yu embodies wu, which is associated with physical prowess and the lower classes. "The ideal man is supposed to be someone who has both qualities. So in leadership, the emperor sits in the middle. He is not as good a fighter as a wu man, and not as good a scholar as a wen man, but he has the quality to lead both," Professor Louie says. |  Professor Kam Louie |

||

Wu, wen and women |

|

Chinese women are typically portrayed as being attracted to wen men, who as scholars would have status and security. Wu men prefer the company of other men and dislike woman because they see them as a distraction. "It's loyalty to the brotherhood. You don't betray your men," he says. That loyalty gives rise to 'homo-sociality' in which the men have significant emotional and physical relationships with each other. In contrast, Western masculine icons such as James Bond tend to operate by themselves and do not mind giving in to the temptations of women. The Chinese brotherhood also is characterized by a strict hierarchy. "In English you have the roundtable, where nobody is boss and everyone is equal. But in Chinese, even in the structure of the language it's not an equal relationship. In Hong Kong crime movies, dai lo or lo dai, means boss, the person who controls you. Even if you say 'older brother' in English, it doesn't have the ring of the triad leader," Professor Louie says. |

|

Changing views |

|

Nonetheless, the traditional bounds of wen-wu have been changing and modern consumer culture is altering the ideal of Chinese masculinity. "For centuries the cultural ideal explicitly excluded money, so the merchants traditionally were in the lowest position in status, even lower than peasants in theory. But what's happened now is money is everything. It's quite desirable to have money, and if you get that through your education, that is fine and proper." Notions of who can possess wen-wu are changing, too. Foreigners in the past were deemed incapable of possessing wen-wu but now they are celebrated for their poetry readings and martial arts skills. Even women can have the necessary qualities as evidenced by their acceptance in the halls of power. The wen-wu ideal is also travelling overseas through martial arts films and computer games.

Professor Louie sees these changes as integral to Chinese culture. "Chinese society is always full of dilemmas and ambiguities that it can't resolve, so it tolerates them. Because it's not so strict, at one time you can say the merchant is the lowest class and at the next, that it's glorious to make money. The ambiguity enables things to change." Theorising Chinese Masculinity: Society and Gender in China by Professor Kam Louie is published by Cambridge University Press. |

| Back | Next |