| |

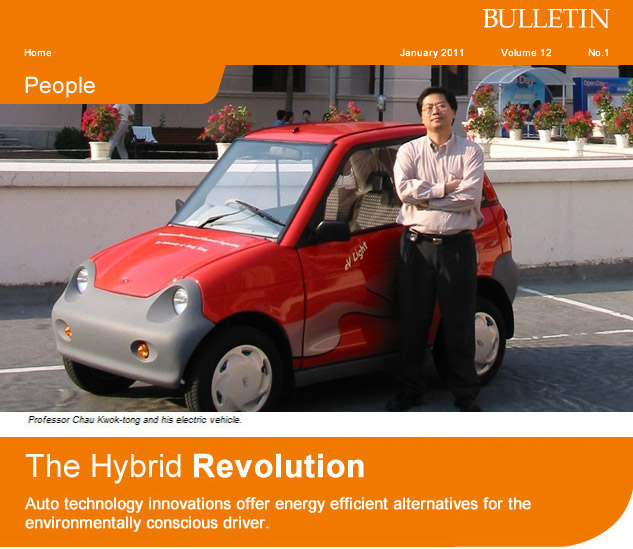

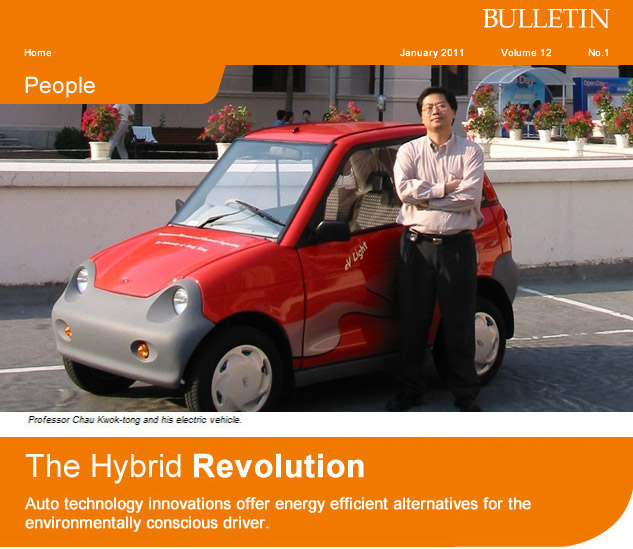

Although developing an electric car may seem an ironic choice of career for a man who doesn’t drive, creating a fuel-free form of transport is exactly what Professor Chau Kwok-tong has devoted his working life to achieving.

His love affair with electric vehicles began as an undergraduate, when he was inspired by the work of Professor C.C. Chan (later to become his PhD supervisor), who established HKU’s International Research Centre for Electric Vehicles, in 1986.

At that time there were no electric vehicles available on the market and the only way to conduct research was to build their own car. Together they went on to write a book, in 2001, summarizing their work and Professor Chau has published more than a hundred technical papers.

Since Professor Chan’s retirement Chau, a Professor in the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, has remained passionately committed to advancing the technology of different kinds of electric vehicles.

“Right now I’m focused on hybrid-electric vehicles, how to co-ordinate the driving force from the engine and the electric motor,” he says. “There are two major families right now in electric vehicles; one is battery electric vehicles, the other is hybrid – this means it has an engine and also an electric motor.”

“At the moment the commercially viable one is the hybrid vehicle. The popularity of pure electric vehicles (EV’s) is hampered by the price of the battery, which can often cost half as much as the vehicle itself, and only last half as long.”

“On the other hand in hybrid vehicles, the battery is only about one third, or one fourth, of the cost, making them far more attractive to the consumer.”

Although his research covers all electric vehicles, at the moment Professor Chau is working on hybrid power propulsion. “In hybrid vehicles the power comes from a motor and the engine,” he explains. “But how do you co-ordinate them to ensure that the fuel economy is the highest, or that the emissions are the lowest? This is our aim.”

Professor Chau, who recently delivered a seminar on the history of EV’s points out that the electric vehicle was first developed in 1834, almost 50 years before the conventional car, but its performance was rated poorly and was abandoned in the 1950s. Later, the energy crisis of the 1970s and increasing air pollution resurrected the dream of a clean and efficient form of transport, but EVs remained poor performers.

All that changed in 1997, when Toyota made its momentous breakthrough with the hybrid car. “Previously,” Professor Chau explains, “hybrid vehicles had been very complicated – combining the engine and motor was a very complicated task that no-one was able to solve, until Toyota provided a new method – the hybrid synergy drive. After that, other car makers used similar methods – Ford and General Motors also produced hybrid vehicles,” he says.

“This system is very good but it still has some problems. It’s based on mechanical gears which combine two driving forces, one from the motor and one from the engine. My research right now is trying to use electrical means to combine them, rather than mechanical gears. The mechanical gear definitely has a disadvantage, there’s wear and tear from friction. So I am exploring two alternative methods; one is by electrical means rather than using gears, because with electrical machines the rotating part and stationary part have no physical contact, so there’s no wear and tear, so less maintenance. The other method, which is a new idea, is using magnetic gears. It’s based on the mechanical gear system, but there’s no contact at all, just the use of magnets.”

Despite the setback experienced by the Toyota Prius, hybrid vehicles are likely to become mainstream within the next five years, says Professor Chau. “In the last five years the development of hybrids has been very fast and public acceptance is very high, people use hybrids because the oil prices have increased.”

“The major reason hybrid vehicles are so successful, compared with EVs is that they are not so expensive, also EV’s need a place to recharge and each car needs eight hours, this is not feasible.”

“With hybrids the entire charging is done by the motor itself, it also works as a generator to charge the battery. However, this is not so efficient so the new family of hybrids, the plug-in hybrids, allow you to use the plug to charge it whenever possible.“

Hong Kong has long been open to using alternative energies for public transport. Our tram network dates back more than a century, while our MTR system is the envy of cities across the globe. And, with scholars like Professor Chau beavering away in the lab perhaps we can look forward to a greener cleaner future on our roads as well. |