|

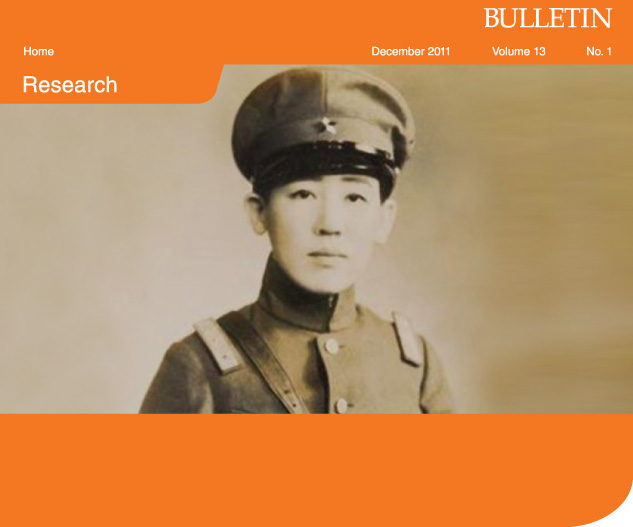

From Mata Hari to Yoshiko Kawashima the idea of the sexy female spy has enthralled the perpetrators and purveyors of popular culture. We may believe we live in more sophisticated times but women spies are still viewed as dangerous femme fatales, as witnessed by the recent furore over the exposed Russian informant, Anna Chapman. No less controversial is the role such women played in China's 20th century history. Foremost amongst them is Yoshiko Kawashima, the Japanese/Manchu princess whose extraordinary life and exploits have been popularized in film and books, and Zheng Pingru, said to be the inspiration behind Eileen Chang's novel, Lust Caution. Now the female spy has moved beyond the popular imagination and into the realms of academia as the subject of new research being conducted in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures (Modern China Studies). Professor Louise Edwards' interest was piqued when glancing through a women's journal from the 1940s. The beds of the enemy "In 1940s China the Communist Party published a journal called Women of China from its base in Yan'an," she explains. "At that point women Party members were actively critiquing party operations with one article headlined 'Our Place is at the Frontlines of the Battle not in the Beds of the Enemies.' The complaint was that when young women joined up for the war effort they were frequently encouraged to go into espionage. The article complained that women were being used and abused not only by the Communists but also the Nationalists. They said women wanted to carry a gun and kill, not just trade sex for information." "I thought it was amazing that someone would actually talk about this so openly. There was a follow-up article which continued in a similar vein saying women couldn't join the military if they were married or had children and that this was discriminatory in terms of employment. The reason for this was because there was little use for women beyond spying, and if they were married, or had kids, then that would cause problems because they 'belonged' to another man." "The author of that particular article pointed out that women were giving themselves abortions, hiding marriages and pretending that they didn't have kids to join up and that this was a health issue as well as a women's issue." "That got me thinking about what happened to these women after the war, after 1949." However, information on female spies is scant." "It appears to have been completely denied as a history." A fictional insight Professor Edwards has recently completed an article, forthcoming in the journal China Quarterly which considers a fictional short story When I was in Xia Village, written by Ding Ling in 1941. It provides an insight into the lives of the Mainland's female spies. "The story is about a young woman who is used as a sex spy by the Communists and is later disdained for this role when she returns to her own village. I looked at the ways in which the story has been interpreted and reinterpreted in the last seventy years." "In 1956 people were saying there's no way this character could have been a sex spy, our Communist Party would never have used women this way, they had legitimate means without having to resort to such underhand methods." "In 2003 the story was adapted into a movie where the character blows herself up with a grenade in the Japanese 'comfort' camps. So she has become a chastity martyr in the old Qing Dynasty style." "It's all about tracing how people have managed the idea that their glorious government has actively made use of these women in these roles. They go from denying, to trying to explain it, and even treat the character as if she were a real person saying that the author has misrepresented her – as though the fictional character actually existed." Lust Caution Confusion A similar confusion surrounds Ang Lee's film, Lust Caution. The main female character is a spy for the Nationalist Party who, at the end of the movie, falls in love the man she's supposed to be entrapping and so betrays the Chinese forces. "Some Mainland critics confused reality with fiction. They said you are talking about Zheng Pingru (an actual Nationalist Party intelligence agent during World War II), and you've slandered her name by saying she was a sex spy." "They get the reality and the representation confused constantly. They accused Eileen Chang of also misrepresenting this character." "So there's concern about sex spies and I wanted to look at why it causes such anxiety when everyone knows it goes on. How do governments cope with the fact that they are trying to establish themselves as a legitimate moral force, claiming they have the right to rule because they have good morals but are then using underhand methods that most people associate with the enemy, not with themselves." Professor Edwards intends to continue researching Zheng Pingru and Yoshiko Kawashima – who famously kept a private army and frequently passed herself off as a man. |

"Pingru is mixed Japanese/Chinese parentage and Yoshiko was adopted Japanese so I'm interested in the question of split loyalties, the idea of treachery and race and sexual orientation, and where the loyalties lie. Because a lot of the sex spies seem to have the problem that nobody trusts them. If you're having sex with the enemy can you really be trusted with your task because maybe you'll fall in love like the Lust Caution character and then who do you really belong to?" |

|

|

|||

| Next | |