|

|

Hong Kong in the early 1900s was perhaps not the first place one would think of as a site for a new university. There were few children – only 12 per cent of the population was aged five to 15 – and the population was transient. But times were changing and its leaders were determined to be at the vanguard. Increasing numbers of young people from China were travelling to North America and Europe for a Western education, an endeavor that was costly and required prolonged separation from families. At the same time, other nations such as Germany were laying plans to establish universities on Chinese soil. Why not have a university in British Hong Kong that maintained a standard equal to English universities, taught in English and was secular (missionary groups were also planning universities at this time)? As the Governor, Sir Frederick Lugard, put it: "It will . . . promote a good understanding and friendship between British and Chinese. It will afford a cheaper means of acquiring higher Western education for Chinese, without exile to the West for a long period, involving denationalization and disunion from their parents and people." |

| A regional university at first | |

This goal led to the University of Hong Kong opening its doors in 1912. It had two faculties, Medicine and Engineering (Arts was added in 1913) and 54 students, and offered a four-year curriculum. It was a purely teaching institution, drawing students from China, other British colonies such as Malaya and, less so, from Hong Kong. The focus was on producing doctors, engineers, teachers and administrators for the region and while that remained the aim, the curriculum focus and student body began to change in the years leading up to the Second World War. Student enrolment had increased to more than 600, but the intake from the Mainland was shrinking while local student numbers increased (though they were still only 34 per cent of intake in 1938). Academically, there was recognition that more specialized units were needed to teach subjects of importance to the region and the times. A Department of Chinese was formed in 1927, while in 1939 the Faculty of Science was hived off from the Faculty of Arts (which continued to teach business, law and other subjects not covered by the other faculties). Just before the war, there was talk of moving to a three-year degree and even re-positioning the University. Senior administrators began asking, should the University face towards Hong Kong or China? | |

|

|

||

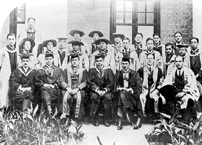

| The first batch of engineering graduates with professors in 1916. | Medical graduates at the Chemistry Building, 1958. |

Post-war changes |

|

The answer to that question did not come until after the war, which had brought classes to a halt as the Japanese took over the grounds and killed or imprisoned many staff. But the post-war turmoil in China and the influx of refugees made the response inevitable: HKU had to put all energies into helping Hong Kong to cope. More infrastructure and medical and social services were urgently needed. The University also saw greater competition for places as the influx from China included young people keen to further their education. In 1954 the curriculum was reduced from four years to three, in part to allow more students to be admitted and to bring HKU in line with other Commonwealth universities. Graduates during these years played a critical role in Hong Kong's development, taking up leadership posts in all sectors of society, including government, business, law, social services and culture. They helped to re-build Hong Kong and laid the groundwork for the emergence of a more stable society, and thus a more stable place for the University to develop. Student numbers increased steadily and by 1970 there were more than 3,000 students. More students meant more staff and a wider range of specialties, which helped to drive the expansion of faculties in the University. The Faculty of Social Services opened in 1967, followed by five more new faculties leading up to 2001. The number of Bachelor degree programmes increased from three in the 1970s to 37 in the 1990s, and postgraduate degree programmes from five to 41 (in 2011 they numbered 33 undergraduate and 109 postgraduate programmes). | |

The Great Hall inside Main Building before the war. The Great Hall inside Main Building before the war. |

Ruins of the Great Hall in 1945, renamed as Loke Yew Hall in 1956. |

A curriculum for a globalized city |

|

The broader range of offerings also reflected the needs of a more complex, sophisticated society. Hong Kong was shifting from a manufacturing centre to a provider of financial and related services, its population was better educated and aspiring to a better standard of living. The city's prosperity and growth was also, once again, becoming tied to its position as a regional centre. The University began revising its curriculum in 1997 to meet the standards and needs of this evolving, globalized city. Greater emphasis was placed on language enhancement, IT literacy, cultural sensitivity and bridging the arts-science gap. Combined degrees were introduced so students could emerge with more than one skill set. More non-local students were admitted and collaboration was developed with institutions in Mainland China. | |

|

These trends have been strengthened and formalized in the new curriculum, which will be fully implemented in 2012. The undergraduate degree for most studies will lengthen from three years to four to give students a broader education that supplements more specialized knowledge studies. The new Common Core Curriculum requires them to look at issues in today's world from multi-disciplinary perspectives, to consider how to tackle ill-defined problems, and to consider their place in a globalized society. Much as it did in its early days, the University is educating leaders and professionals who can serve both Hong Kong and the region. But this time it is doing so with its roots planted much more firmly in Hong Kong and its sights fully developed to accommodate local, regional and global perspectives. |

| Next |