| A Room for Debate |

|

| The jailing of dissident Liu Xiaobo motivated the Faculty of Law to promote deeper discussion on China’s constitutional development and reform. |

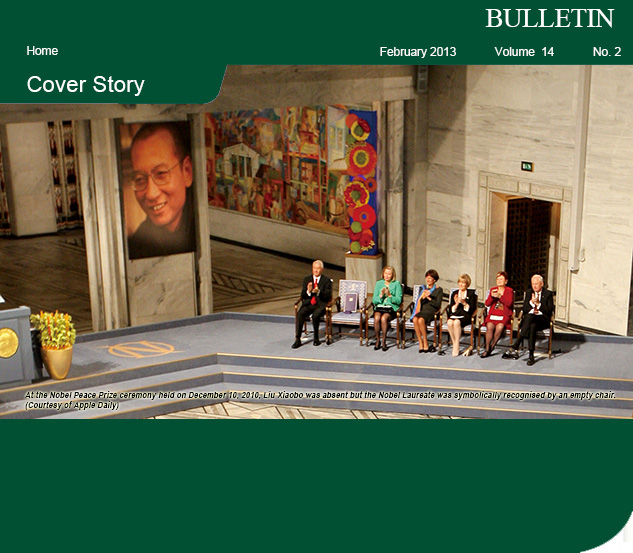

When Liu Xiaobo was jailed for 11 years in 2009 for co-authoring Charter 08, a manifesto calling for the reform of China’s constitution and the end of one-party rule, there was a global outcry. Liu ended up being awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010. Closer to home, the outcry was just as intense but there was only one place in Greater China that scholars, lawyers and others concerned could gather for frank discussion: Hong Kong. The Faculty of Law quickly realised the city’s position and organised a series of conferences and seminars that attracted people directly involved in the case, such as Liu’s lawyers and other Charter 08 signatories, as well as academics from China, Hong Kong and abroad who were interested in the case in the context of China’s historical political development. The result of their deliberations is a recent publication, Liu Xiaobo, Charter 08 and the Challenges of Political Reform in China, published by Hong Kong University Press. Professor Fu Hualing organised the gatherings and co-edited the book which includes a statement of Hong Kong’s importance to the debate. “Hong Kong is the only place where Liu Xiaobo and

Charter 08 can be freely, extensively and seriously discussed on Chinese soil,” it reads. |

|

Bringing issues into the open “These are academic events, this is an academic institution,” Professor Fu says. “We’re not doing political mobilisation but providing a forum where people can talk about their different ideas and bring the issues out into the open. The issues we are working towards are rule of law and democracy – whatever it means. We need to keep the debate alive.” Contributors write on both the specifics of Liu’s case and its larger historical perspective. Professor Fu himself wrote about the development of the rule of law in China over the past 30 years and how Liu’s case fits into that. The rule of law and legal rights have strengthened as China’s economy has opened, and vulnerable groups have subsequently used the law to pursue their rights and challenge the central government. The government has regarded this development with alarm and has struggled to contain these demands, leading it to harden its position and reduce the potential for consensus-building, he says. But at the same time the Communist Party itself is not immune to changing demands and some members are leaning towards reform. The prevailing situation explains both the harsh judgement on Liu and the important differences in his case as opposed to challenges to the government in the past, Professor Fu says. |

Liu Xiaobo, Charter 08 and the Challenges of Political Reform in China published by Hong Kong University Press |

|

“Hong Kong is the only place where Liu Xiaobo and Charter 08 can be freely, extensively and seriously discussed on Chinese soil.” |

||

| Professor Fu Hualing |

|

Singling out Whereas previously the authorities prosecuted everybody involved in a perceived challenge – tens of thousands of Falun Gong practitioners were detained, for example – in the case of Charter 08 only one person was prosecuted, Liu. Liu was an easy target because he was co-ordinator of Charter 08, had been in and out of detention since 1989 and had overseas connections, which the Communist Party regards as suspicious. “There would have been very serious repercussions if they had prosecuted all 300 people [involved in Charter 08],” Professor Fu says. “These people are different from previous cases, they have high-standing in society. They are working in the professions, in academia, they are retired government officials. It’s much more a rebellion within the party system than an enemy force outside, so it makes it hard to prosecute those people without paying a high cost.” Also, following Liu’s jailing “the prosecution was so busy coping with international criticism, I don’t think they had much time to deal with others in China, to harass them. Many of these people had a setback, maybe for a few months, but then they re-grouped and started again.” “The Party is evolving although it is still very authoritarian. When push comes to shove they will say, who cares, we have a regime to save.” Zigzag direction Nonetheless, Professor Fu sees a system in transition. While the government enjoys increasing confidence in the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis, a consensus is also building that democracy would be a good thing for China. The question is how to get there. Charter 08 proposed peaceful incremental change towards greater civil society mobilisation – it was not a call to end the party state now, but to prepare for that end. “China is moving forward but it’s a zigzag,” Professor Fu says. “It’s similar to marriage. If you have no love any more, it’s difficult to pretend for too long. In terms of the relationship between the state and society, you can’t force people to say, yes, you have the power. If you want legitimacy you have to govern by consent. The people need to agree.” “We provide a forum for people to talk about these ideas and debate. Some are more critical [of Liu and

Charter 08] so we bring the issues out, we keep them alive. I see myself as part of this process of contributing to that debate.” |

Demonstration in Hong Kong to call for the release of jailed Chinese dissident and Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo (Courtesy of Apple Daily) |

| Back | Next |