| In Defence of Hong Kong’s WWII Pillboxes: The Truth about the Gin Drinker’s Line |

|

| A team from HKU have done a study on British and Japanese WWII military installations in Hong Kong for the purpose of preserving this important historic heritage – not a team of archaeologists, but a team of architects, planners, surveyors and enthusiasts. |

|

Tai Hom Village Pillbox | “We’d like the government to form a proper conservation policy to protect the Shing Mun site and to promote interest in it.” |

|||

| Dr Lee Ho-yin | ||||

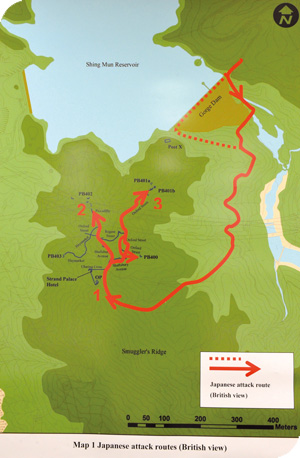

The main aims of the study were two-fold: One to spark interest and two to conserve. Project organisers Professor Lawrence Lai and Dr Daniel Ho both of the Department of Real Estate and Construction, and Dr Lee Ho-yin of the Department of Architecture worked alongside an interdisciplinary team of experts, as well as enthusiasts from the community. They set out to study British and Japanese World War II military installations in Hong Kong and over several years conducted land surveys on key military structures. Scattered all over Hong Kong, but often largely unnoticed, these structures included gun batteries, block houses, pillboxes, firing trenches and tunnels along the defence lines at war and at major battlefields. The team identified and mapped a total of 93 pillboxes along the so-called Gin Drinker’s Line, a defensive system known as the ‘Maginot of the East’, which ran across the New Territories from Gin Drinker’s Bay (Kwai Chung) to Port Shelter to defend against enemy invasion from the north into the Kowloon Peninsula and over to Hong Kong Island. They also measured and mapped the incredible and extensive network of tunnels of the Shing Mun Redoubt above Shing Mun Reservoir – a bastion of the Gin Drinker’s Line where an important and controversial battle which saw Japanese soldiers overrun the Redoubt in just three hours. After the fall of the Redoubt, the British defence of Kowloon unraveled and they quickly evacuated the Kowloon Peninsula. As a result, the Japanese were able to conquer the rest of the Mainland with little trouble. Over the years there has been some arguments about how and why this battle was lost so quickly – the team’s research threw up some informed hypotheses. ‘Evacuation inevitable’ “The British knew that if Japan invaded, the evacuation of Hong Kong was inevitable,” says Professor Lai, “but strategy was to deny Victoria Harbour to the enemy. It was thought that Shing Mun would hold for a week. To be fair it was undermanned – the Japanese had a regiment of battle-hardened soldiers who’d seen action at the infamous Battle of Nanjing, the Allies had about 40 Royal Scots.” “Having studied the layout, what we now think happened is that the Japanese attack force realised that the Redoubt was unprepared (the observation post [OP] was facing the wrong direction), and took the initiative to attack in darkness, easily taking the Redoubt. They held 20 guys captive in the OP.” |

|

Professor Lawrence Lai, Department of Real Estate and Construction | It’s a fascinating story, and the team hope their findings will spark renewed interest in this period of Hong Kong’s history. “The ultimate aim of the project is to conserve these structures,” says Dr Daniel Ho. “We wanted to arouse people’s interest and thereby encourage the authorities to put in place proper conservation measures to protect them. To do so we needed the facts, so we set out to map the tunnel system and the pillboxes.” Dr Lee Ho-yin adds: “We’d like the government to form a proper conservation policy to protect the Shing Mun site and to promote interest in it. Now, it’s totally open so hikers and weekend wanderers roam all over it – inevitably some damage has been caused.” |

Tunnel system |

Acknowledging that Hong Kong’s reputation for preservation and conservation is poor, the three men point to Mainland China’s policy of using military heritage as centres for civic education and cultural tourism, citing the war museum at Harbin, which was the base of Japan’s 731 Regiment, and the German fortifications at Qingdao where there was ferocious fighting against the Japanese during WWI. Even Macau has done a better job in preserving its recent western military heritage. Says Dr Daniel Ho: “There are books on what happened during the Battle for Hong Kong, but these have been done from a historical perspective and not a factual one. There were no accurate maps or plans of the pillbox sites.” Adds Dr Lee Ho-yin: “Mapping actual cultural resources is now seen as a very important part of cultural research and protection.” Asked why the government has not done this, he is cynical: “I think the government hasn’t worked out how to make money from it – there is a lack of long-term vision in this area. However, if they look at overseas examples, conservation can bring benefits – people are interested in history. It attracts tourists.” Dr Daniel Ho continues, “And not just tourists, Hongkongers should be more interested in their recent history. If the site is properly preserved and protected, we can make better use of the site for the public. The tunnels in the Shing Mun Redoubt are very accessible, but at the moment they are in danger of being accidentally damaged by hikers.” It seems their work has produced results already. “The Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department is renovating their mini museum-tourist centre at Shing Mun with a view to disseminate information about the Redoubt, and didn’t know about our research,” says Professor Lai. “Dr Lee Ho-yin put them in touch with us and we’re exchanging information to help create a museum which shows, amongst others, the team’s findings.” And what is the conservation planning angle? Says Professor Lai: “At present, there is no single government map that shows accurately and comprehensively the key military installations. We hope our findings will provide information for incorporation in government survey maps and town plans for the purpose of conservation development.” |

|

|

| Japanese attack routes at Shing Mun (British view) | Japanese attack routes at Shing Mun (Japanese account) |

|

Role of HKU students There is also much historic interest from HKU’s point of view. At the critical battle on Hong Kong Island at Wong Nai Chung Gap, the invaders suffered high casualties due to two pillboxes held by members of the No. 3 Company of the Hong Kong Voluntary Defence Corps. Some members of this and other companies were HKU students, many residing in Ricci Hall. GIS analysis there has provided further evidence on the historicity of the bravery of the defenders and effectiveness of the pillboxes in the battle. Their research will also be used by the University today. Says Professor Lai: “Our press conference – which was held on December 8 last year, the 70th anniversary of the Battle of Hong Kong – was a vehicle for Knowledge Exchange activities.” It achieved its objectives of attracting government and media interest. The Japanese media were particularly interested in the kind of the on-going research. He and Dr Daniel Ho are now working on a book about the pillboxes of Gin Drinker’s Line. “We’ve also used the findings from this project to launch a new Common Core course for the next academic year,” concludes Professor Lai. “We hope this will all help to kindle interest in these sites. Hongkongers should be proud of their history.” |

Markings on the tunnel wall |

| Back |