| Tripped up by the Tongue |

|

| The sources of language disorders, especially in Chinese and bilingual speakers, are being investigated by our researchers. |

|

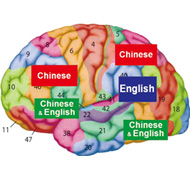

Imagine the nightmare of a stroke victim who can understand speech but can’t produce intelligible sentences, or produces sentences but can’t understand speech. Or a child of normal intelligence who struggles to read and write. These scenarios are driving research at HKU that seeks to understand language development and disorders in Chinese and bilingual speakers, as well as the workings of the brain. Professor Tan Lihai, Director of the State Key Laboratory of Brain and Cognitive Science, was recently awarded RMB39 million (HK$47 million) from China’s 973 Program to study the neurophysiology of Chinese language users, the first Hong Kong-led project to be funded by the national research programme. And Professor Brendan Weekes, Chair of Communication Science and a world expert on the language disorder aphasia in bilingual speakers, is investigating treatment and rehabilitation. |  Professor Tan and his team discovered the diversity of cortical regions for languages by investigating the neurodevelopment of normal Chinese language users. |

| More language disorders in Chinese

Professor Tan’s research is driven by the fact that Chinese speakers with brain damage suffer far more from language disorders than people with similar damage in the US. Some 70 per cent of Chinese with brain palsy, such as children born with cerebral palsy, experience language disorders against 20 per cent of Americans. Similarly, 70 per cent of Chinese speakers suffering brain damage due to stroke, tumours, epilepsy or other diseases experience language disorders against 50 per cent of Americans. “Why do so many Chinese have language disorders? Possibly it’s because there are more regions in the brain involved in Chinese language processing,” Professor Tan says. Previous research has shown that native Chinese speakers use more areas of the brain for speaking and listening than English speakers in order to handle the tones. Professor Tan’s lab has also shown they use different areas for reading. However, unlike alphabetical languages, the genetic basis of the Chinese language is not well understood. Professor Tan is therefore leading 25 experts from Hong Kong, China and the US to investigate the neurodevelopment of normal Chinese language users and those with language disorders such as stuttering and dyslexia. They will also look at how the different brain regions interact in language activities, and the candidate genes behind Chinese language disorders such as dyslexia. “The genetic study will help us to have early identification of patients with language disorders so we can have early intervention,” he says. Translating the findings into clinical approaches is also a goal and could be significant for other researchers such as Professor Weekes and his colleagues, who are among the world leaders in treating bilingual speakers who suffer from aphasia. The special case of bilingual speakers Aphasia is the loss of the ability to produce or understand language and it results from strokes, dementia and other diseases. There are obvious differences in how aphasia manifests itself in Chinese versus English speakers and more insights into language processing could help their treatment. For instance, when the Broca’s area of the brain is damaged, it affects the ability to produce language, including different verb tenses which is problematic for speakers of European languages but not Chinese. If the damage is in the Wernicke’s area of the brain, the ability to understand language is affected, including tones, which makes it much more difficult for Chinese speakers. But what’s even more important, says Professor Weekes, are the commonalities seen. “The features of different languages do embellish the kinds of problems we see, but the general point is that problems of fluency and dysfluency occur across languages.” His research has helped to demonstrate this by studying people who speak more than one language. It turns out that rehabilitative training focused on one language can bring improvements to the other language even if the languages are very dissimilar, such as English and Chinese. “This shows that what is critical is the cognitive process and exercising the brain,” he says. “I study bilingual aphasia to understand the brain and how it works rather than only looking at how to make people better. What does aphasia tell us about how the brain is organised?” | |

|

|

|

Larger brain matter One feature of interest is that bilingual or multilingual speakers use a ‘switch’ in their brain to suppress one language while speaking another. This area is larger in their brain than in monolinguals‘, but it can be affected by brain damage and thus affect language processing. Some multilingual patients may speak one language one day and another the next, while others may mix the languages together into an incomprehensible jargon. Language recovery seems to depend most on which language was recently dominant, so someone whose first language was Cantonese but who mostly uses English in their professional and personal life may recover English first. Professor Weekes’ laboratory has also been working with Professor Jubin Abutalebi of Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, who is studying the brains of healthy bilingual people in Hong Kong and monolingual speakers in Mainland China and Italy. The expectation is that Hong Kong bilinguals will have more gray matter, which could delay the onset of another brain disorder, dementia, and thus have important implications given the ageing population and the lack of any effective drug treatments for the disease. “Every intellectual activity we do as we get older keeps our neurons working so they are more resistant to neuron degeneration. Bilingualism is one of the strongest inducers of this,” Professor Abutalebi says. “Think of how much money the health system could save if we delayed dementia by one or two or three years. Investing in language learning, even in adults, could protect against cognitive decline.” The evidence to support that, as well as the insights emerging from Professor Tan’s and Professor Weekes’ research, may well result in measures that improve the quality of life for people in China and around the world, particularly as they get older. |

| Back |