|

Rub your finger on the same spot for 30 minutes every day and over time, the area of the brain associated with detecting that sensation will get bigger. And so it is with meditation. People who regularly practise meditation have been found to have changes in the volume of their brain’s gray matter and activity as compared to novice meditators. “Experience changes the brain and meditation is itself an experience,” says Professor Tatia Lee Mei-chun, May Professor in Neuropsychology, whose research is showing that different types of meditation can affect different areas of the brain. While most researchers have studied focused attention meditation, which centres on one object or bodily sensation such as breathing and affects the area of the brain involved in concentration, Professor Lee’s team have studied loving kindness (LK) meditation, in which practitioners elicit compassionate feelings for themselves and others. They have found that this form of meditation also affects the brain, but in the regions involved with regulating emotions and mood. Such findings are generating excitement outside of neuroscience because they hint at the potential for meditation – also called mindfulness – to improve people’s daily lives. In medicine, for example, it is seen as a way to help medical students look beyond clinical knowledge and consider the conditions of both the patient and themselves. The Faculty of Medicine has made mindfulness a key component of its medical humanities programme. “The skill of mindfulness,” says Chair Professor Chan Li-chong of the Department of Pathology, “is to bring the mind back to the present moment and stop it from ruminating on the past or worrying about the future. And certainly you can use mindfulness to engage in the things doctors do, like mindful communication with patients, active listening, and being aware of one’s emotions without making judgements when facing an angry patient. Often we terminate the conversation with the patient because we have made a judgement already.” The Centre of Buddhist Studies has also shown that secondary school students can benefit from a practice that for centuries has been largely associated with spirituality. The Centre ran a programme in local secondary schools in which students’ ‘sense of coherence’ – their ability to comprehend, manage and find the meaning of life – was enhanced by the interaction of Buddhist teachings and workshops which included meditation. “Sense of coherence has been strongly linked to both physical and mental health outcomes. So if we can enhance it, this would enhance students’ ability to handle stress,” says Venerable Sik Hin Hung, Acting Director of the Centre of Buddhist Studies. In the pressured, time-constrained conditions of modern living, taking a moment to breathe deeply and calm the mind may prove to be a welcome boost to our well-being. |

| Neuroscience and Meditation |

||

| “Different forms of meditation have different effects on the brain.” | |||

| Professor Tatia Lee |

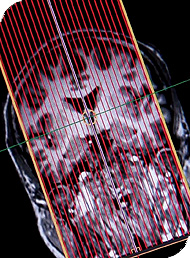

Professor Lee began studying the neuropsychological effects of meditation in 2006 and is patiently building up data that shows those who meditate have different brain architecture and functions than those who do not, and that different types of meditation have different effects on the brain. Working with experienced practitioners of both focused attention and LK meditation, as well as novices, she has been able to pinpoint differences in brain volume and in the blood oxygen-level dependent (BOLD) signal which indicates brain activity. In one study, participants were asked to respond to specific signals on a computer screen and ignore irrelevant signals. Those experienced in focused attention meditation were the best performers at this concentration task. Interestingly, LK meditators did not perform well, although both groups did better than the novices. However, LK meditators showed marked differences in brain activity in another study that asked them to look at emotional, or affective, pictures. |  Coronal view of the brain |

“We couldn’t say who performed better at that task because we didn't have behavioural anchors, but when we looked at LK meditators compared to the control group, their BOLD signals were different and so were the structures of their brains that correlated with the emotional processing network in the brain,” Professor Lee says. What this means is that the effects of meditation are more complex than previously thought. “Different forms of meditation have different effects on the brain. So the implication is that we may use different forms of meditation for a specific purpose.” More research is needed to identify the full effects and potential of LK meditation, but the intuition is that it may help meditators to arrive at a tranquil and calm state. If so, it could have significant implications. “There is a high percentage of people in our community who are affected by emotion disregulation – depression, anxiety, you name it,” says Professor Lee. “Maybe down the road we can look into this. Meditation seems promising for possible clinical application.” |

| Medical Introspection |

||

| “It’s not just that students do the meditation exercise. They appreciate how it helps them.” | |||

| Professor Chan Li-chong |

| It also has promise for application with clinicians, as the Faculty of Medicine is finding. Last year the Faculty completed a two-year project to train frontline hospital staff in mindfulness. Now, it’s the turn of medical students.

Mindfulness has been incorporated into the developing medical humanities curriculum, which aims to help students develop resilience and well-being so they can better deal with the stresses of their occupation. The curriculum also covers narrative medicine (focusing on doctors’ and patients’ stories) and consideration of such issues as culture, spirituality and healing, and death, dying and bereavement. Pilot projects held last summer and this winter taught students how to be present and mindful in the here and now, even when walking and eating, and to apply this awareness when dealing with patients. “The students say they find it very helpful to be listened to and they find they are understood when someone listens without interrupting them,” says Professor Chan. |

|

“Conversely, they find it difficult to listen to someone without interrupting them. But if you really pay attention when a patient is talking, you will understand more about their situation.” “It’s not just that students do the [meditation] exercise. They appreciate how it helps them, their relationships with their peers and family, the way they look at a patient who complains or talks to them, and how they can at least be there to listen to them.” That effect of mindfulness training supports the wider goal of the medical humanities curriculum to promote medicine as something deeper than just a good understanding of biomedicine. Dr Julie Chen Yun, Assistant Professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care, says: “I think for a long time, it has been taken for granted that students would automatically absorb this other side or pick it up. To an extent they do through role modelling, but increasingly we’re finding that it’s something that can be nurtured. If you start early and put it in the curriculum in such a way that recognises it is important, i.e. by making it compulsory, then it sticks in their mind. They value it more if they see that we value it.” |  From left: Ms Venus Wong, Professor Chan Li-chong and Dr Julie Chen Yun |

| Finding Deeper Meaning |

||

| “We tried to help students find the meaning of life by introducing them to the Buddhist understanding of life and at the same time teaching them how to manage life through Buddhist practices including obviously mindfulness practice.” | |||

| Venerable Sik Hin Hung |

What if this training started even earlier – before students arrived at university, strung out in some cases by the demands of Hong Kong’s secondary school curriculum? That is a question of particular interest this year with the switch to a four-year university curriculum in Hong Kong and the admission of undergraduates who will be one year younger and less experienced than previous intakes. The Centre of Buddhist Studies sought answers through a project in which secondary school students received Buddhist education and interactive workshops to see whether this would improve their sense of coherence. The workshops included meditation, as well as games, outings and other activities. More than 600 students were divided into three groups. One group attended the interactive workshops and received lectures on Buddhism, one group received only the lectures, and one group received none of these. Before and after tests on students’ sense of coherence found a significant improvement for those in the first group who also performed well in their final grades in Buddhist studies. In fact, the ability to benefit from the workshops is correlated with the students’ knowledge of Buddhism, although students who only attended lectures in Buddhism but did not attend the series of workshops did not receive the same benefits. Interestingly, the students in the workshops said meditation was their favourite activity. “We tried to help students find the meaning of life by introducing them to the Buddhist understanding of life and at the same time teaching them how to manage life through Buddhist practices including obviously mindfulness practice,” Venerable Sik says. “You can’t just go to workshops and not study. Or study and not go to workshops, nothing happens. You need the theory and the practice.” The theory and practice intersect in pondering the deeper questions of human existence. Venerable Sik says they played a game in which students rolled dice to see who would get expensive candies and who would get cheap candies. They rolled again for a chance to take other people’s candies, and that was the end of the game. Students were then asked how they felt about the game, whether it reflected the state of the world, whether it was fair, how they might view the game if they had the nicer candies and so forth. “There are situations in life where you are just left with the bad side. How do you deal with it? Just by being angry? Or would you humbly submit? Or can you be happy with a little bit of candy? Obviously you can. There are many things to discuss. Who was in charge of the allotment – somebody else? You? God? Was it just simply luck or something else? This is comprehensibility. You need an environment where you can explore these questions,” he says, adding that the Centre is now seeking funding for a permanent venue to sustain the teachings and workshops for students. You also need an appreciation that these questions matter. The hope is that our scholars’ contributions to the application and understanding of mindfulness will provide evidence and inspire others to explore this ancient but still developing practice. |

| Next |