|

|

| |

|

| |

You don’t see people wearing Hitler or Stalin T-shirts, and you’d likely be ostracised if you did. So why is it fashionable to wear Mao?

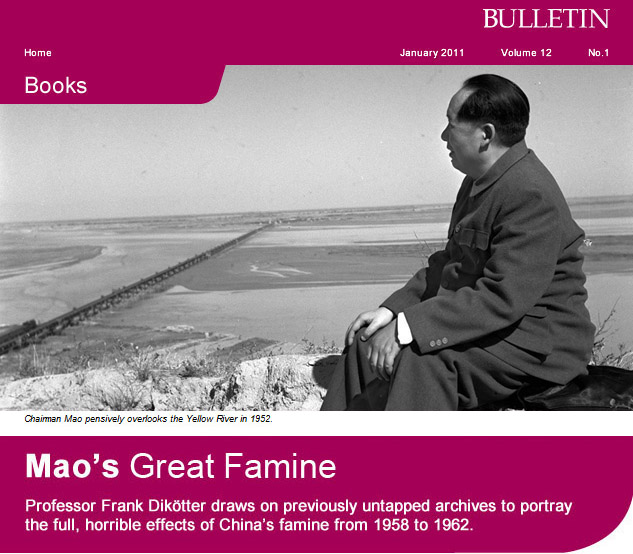

That phenomenon perplexes Professor Frank Dikötter, Chair Professor of Humanities in the Department of History, who has just published a highly-regarded book on the vicious and tragic consequences of the Great Leap Forward, Mao’s Great Famine. He sees a parallel in the reluctance of historians to tackle this subject in depth.

“It’s simply not fashionable to write anything critical of modern China – there’s such willingness to tiptoe around major historical matters like the great famine.”

“It’s hard to imagine how historians got away with it when you compare it with the literature on the Holocaust and the Gulag. Yet it was one of the worst mass murders in human history,” he says.

|

| |

|

|

|

Mao and Khrushchev at the Kremlin in November 1957.

|

|

On May 25, 1958 Chairman Mao galvanised the nation by appearing in front of the crowds at the Ming Tomb Reservoir; the original photo also showed Peng Zhen, the mayor of Beijing, but he was later airbrushed out of the picture. |

|

| |

Professor Dikötter takes the known outline of the famine and fleshes it out with newly-available documents from provincial and county archives that provide a detailed account of the effects of the famine and its causes.

At least 45 million people died – most from starvation but 2.5 million from torture or summary execution and one million to three million by suicide. These are incredible figures considering that 95 per cent of the famine was man-made, he says.

Mao’s ’Great Leap Forward’ forced people to give up private property, join collective farms and toil incessantly in the belief that this would help China overtake Britain in iron, steel and other industrial output and enable the country to repay debts to the Soviet Union far earlier than they were due. Anyone who opposed it was sidelined or worse.

Large quantities of food were shipped out of the country, some of it as food aid, leaving little for China’s populace. In desperation people ate anything they could find, from leaves, soil and roots to poisonous berries and leather. Children were sold and the old and sick who could not work were literally discarded and left to die.

Professor Dikötter’s book describes the big picture and the individual stories of the famine, with particular concern for the fate of rural populations who suffered the most.

“Again and again these farmers have been overlooked,” he says, almost to the extent that their existence has been forgotten in China. “By some strange twist, the efforts of the PRC not to write about this huge catastrophe has had an effect on the archivists in China themselves. They tend not to know about the great famine.”

|

| |

|

| |

|

| Building a cofferdam of straw and mud to divert the Yellow River at the Qingtong Gorge in Gansu, December 1958. |

|

Chairman Mao inspecting an experimental plot with close cropping in the suburbs of Tianjin in August 1958. |

|

October 1958, Breaking stones for the backyard furnaces in Baofeng county, Henan. |

|

| |

|

| |

|

Li Jingquan, leader of Sichuan province where more than 10 million people died prematurely during the famine, shows off a model farm in Pixian county, March 1958.

|

|

Li Fuchun meets several cadres in the suburbs of Tianjin, autumn of 1958.

|

|

Peng Dehuai at a meeting with party activists,

December 1958. |

|

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

Liu Shaoqi tours the countryside in his home province of Hunan in April 1961.

|

|

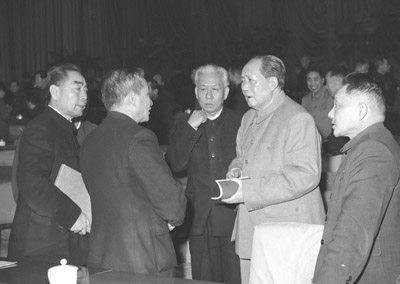

January 1962, from left to right, Zhou Enlai, Chen Yun, Liu Shaoqi, Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping at the party conference dubbed the Seven Thousand Cadres Assembly at which Liu openly blamed 'human errors' rather than nature for the famine. |

|

| |

|

| |

He worked that ignorance to his advantage in his research, digging up as much material as he could when the archives opened in the more liberal atmosphere prior to the 2008 Beijing Olympics.

“I’ve been trained not to assume that when there is an opportunity, that it’s part of a gradual opening up. I remember very distinctly when I was applying for grants for this project that this was a rare moment, a window of opportunity that had to be seized. I’m glad I jumped in then rather than wait for it to open more.”

“I’ve been back to the archives in the past year and in nearly all cases, a certain amount of the material has been reclassified. The whole atmosphere is very much changed and it’s no longer as easy to get access. I don’t think it would be possible to research the book now. The willingness and openness that culminated with the Olympics have gone downhill ever since, including [Nobel peace prize winner] Liu Xiaobo being put behind bars.”

More public knowledge of the famine may not necessarily spell bad news for China’s rulers, though. “Oddly enough, ordinary people tend to think of the regime today in a rather positive way in comparison. It’s not uncommon to hear people say it’s so much better now. So through some very bizarre twists, that catastrophe gives the party some credit today.”

Professor Dikötter’s book has received enthusiastic reviews around the world and he was invited to give 16 talks and numerous media interviews during an autumn tour of Europe and the US. He is now working with his colleague, Zhou Xun, to dig deeper into the Communist Party’s history of the early 1950s and offer a similar account of the repercussions its policies had on ordinary people. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

|

|